Peter Simpson tells the story of the iconic Bedford CA, a van which set new standards when launched, and remained the firm market leader until the Transit arrived.

“You see them everywhere!” So said Bedford’s advertising in the immediate post-war era, and it was certainly 100% true with the CA van range. An instant success from the moment it was launched in 1952, the CA, with its distinctive snub-nosed front, was to remain in production for 17 years, and was an instantly-recognisable, familiar and friendly face throughout the fifties, sixties and seventies and into the early eighties. Look at any period street scene, and chances are they’ll be a CA in it somewhere!

Of course, it was the short, snub-nosed ‘bonnet’ that made the CA so recognisable. Until Ford’s all-conquering Transit arrived in 1966, this was unique to the CA. It wasn’t, however, design for design’s sake. With the engine in the usual position for full forward-control – ie, beside the driver – it must either eat into the loadspace behind it, or restrict the legroom of anyone whose seat is on top of it.

If, though, the engine is at the very front of the van, but with the cab half over it so that the van is semi rather than fully forward-control, it doesn’t interfere with the payload at all. It’s also possible to maintain full side-to-side access and three-abreast seating within the cab. Internal noise levels are also lower than when the engine is beside the driver.

While there was a small ‘bonnet’ within the CA nose, this provided access to little more than the fan belt and radiator top-up. However, because it was quite possible to drive with it open, the ‘bonnet’ could also provide some handy extra cooling on hot days. Most engine maintenance was via a removable cover within the cab, which actually gave pretty good access all-in-all. Although, anything involving cylinder head removal was a bit tricky, and some front-end jobs required the entire front panel to be removed; not always easy on an older van with a bit of rust…

Thoroughly modern

The engine position wasn’t, however, the only respect in which the CA set new standards – in March 1952, it was truly state-of-the-art. The overhead valve engine, too, was new and the latest thing – this was just four months after Austin/BMC’s new A-Series engine had appeared, and less than two years since Ford had launched its first OHV engine, in the Mk1 Consul/Zephyr/Zodiac range in 1950. GM/Vauxhall had developed its 1,508cc OHV, mainly for the new Wyvern saloon, but it was also offering this latest thing in a commercial vehicle! The CA also boasted independent, coil-sprung front suspension (again the same as on the Wyvern), and the cab was designed for ease of access with sliding doors and, as already noted, unimpeded side-to-side access.

With all this modernity, the three-speed gearbox was, perhaps, a bit of a surprise, though this was also something of a GM/Vauxhall characteristic. Believe it or not, a four-speed gearbox was, in theory at least, optional on the Vauxhall Victor, right up to 1972! The column gear change was – at least when new – smooth and precise and, of course ‘three on the tree’ kept the cab floor clear, aiding driver access to the nearside door.

Unsurprisingly, the CA was an instant hit. In part this was down to it arriving as post-war austerity was finally coming to an end. But there can be little doubt that the product itself was excellent, it was the van everyone wanted. At first, just one body length was offered – 154in, with a 90in wheelbase, a choice of 10cwt or 12cwt payload, and a loadspace of 135cu.ft. From January, 1958, a 15cwt version was offered, with heavier-duty tyres and rear springs. The Luton factory produced the CA in plain van form or, as a chassis cowl for specialist bodywork. Of course, there were a lot more versions of the CA in showrooms, but we’ll come back to those a little later…

Significant developments

The original CA had a split windscreen arrangement with a fairly thick, central pillar as a separator. This was mainly to allow both screens to be formed from flat glass; curved glass was still new and expensive to produce. By January, 1959, however, things had changed and, to improve forward visibility, a single-piece curved screen was fitted. At the same time, the front panel was changed to incorporate a small, body-coloured radiator grille, with a chrome trim around the top.

Six months later, however, in June 1959, a new, long wheelbase CA was launched, and the LWB CA (designated CAVL) quickly became the more popular version. Wheelbase and overall length were increased by 12in, load capacity went up to 162cu.ft, and the cab doors were widened and fitted with larger glass. At the same time, the windscreen was changed to match, and the roof stiffened. The SWB version (factory code CAVS) remained in production, and the roof and screen changes were made to both versions, as not doing so would have wasted manufacturing capacity.

This does mean, though, that CAs made between January and July 1959 had a unique and slightly smaller, single-piece windscreen than those made afterwards – and, needless to say, they aren’t interchangeable! It’s the sort of thing you don’t notice until you know about it, or you see the two versions side-by-side but, once seen, you’ll always see it!

The next significant change came in June 1961, when the Perkins 4.99 diesel engine was offered as an option, with an ‘O’ added to the factory designations (CASVO and CALVO) denoting oil engine. With just 40hp on tap, this wasn’t fast, but it was economical, and became a popular option with fleet operators and others using vans in high-mileage but low-speed work, such as door-to-door and short-distance delivery operations. One such was the London Evening News; its fleet of yellow newspaper delivery vans was a familiar sight not just in the capital, but also the Home Counties, as the London evening papers had a significant readership in the suburbs.

Few – if any – original, diesel-powered CAs survive; I certainly don’t know of any so, if you have one, do please get in touch! In part, this is because diesel CAs were usually bought for higher-mileage/hard-use purposes. It’s also true that at eight to 10 years old, a typical diesel CA was often worth more scrapped, and with its engine exported, than as a complete, secondhand van.

The following December, a four-speed gearbox was offered as an optional extra – unusually for the time it was an all-synchromesh ‘box. This unit had been an option on the FB Vauxhall Victor from its introduction in September 1960 though, whereas the car had ‘four on the floor’, the van retained column gear change for three or four-speed versions. In practice, many three-speed CAs were converted to four in later life, using Victor boxes; it’s a straightforward swap.

In September 1963, the Vauxhall Victor (which had by now replaced the Wyvern as the mid-range Vauxhall saloon) engine capacity was increased from 1,508 to 1,595cc, and the CA followed suit. The CA unit continued to be available in low-compression (7.0:1) and high-compression (8.5:1) forms. At this point, the 15cwt version was re-designated at 15/17cwt, presumably due to the extra power from the bigger engine.

The third and final facelift (called, confusingly, the Mk2) was announced in May 1964, though not appearing until January 1965. Again, it was the front that changed; a new, bigger windscreen was fitted, together with an anodised aluminium grille. Inside, the dashboard was redesigned to incorporate a cowl around the instruments. Then, from April 1965, the Perkins 4.108 replaced the 4.99 as the diesel option.

Serious competition

From there until production ended in July 1969, the CA remained essentially unchanged. Its replacement was the CF which, though all-new, clearly took its styling cues from the CA. Around 370,000 CAs of all types were sold and, for almost its entire life, the model was the overall market leader in the 10-17cwt van market. It appealed equally to fleet and individual buyers, the basic product stood the test of time well and, with the wide range of different versions available, there really was a CA for everyone – from the family who needed something with extra space, to the self-employed builder and department store chain.

However, in October 1965, just a few months after the face-lifted CA appeared, the light van market was turned upside-down when Ford replaced its aging Thames 400E with the all-new Transit. It’s sometimes claimed that Bedford was taken completely by surprise by this; I personally find it hard to believe that a company as big as GM could have had absolutely no idea that Ford had something special up its sleeve, though it could have underestimated its impact. The fact remains that the Transit was a massive hit from the word go, and immediately became the van of choice. And what a choice there was – six models ranging from 12cwt to 35cwt, and 44 different factory versions.

It took Bedford four years to respond with the CF – a delay which does add credence to the suggestion that it had been caught napping, at least to some extent – and the fact that nothing was done to make the CA more competitive tends to suggest that it was very much a case of all hands on to the CF deck. That four-year gap was, however, crucial in allowing Ford to secure the Transit’s dominant position; a position it’s retained ever since.

The Kent connection

As mentioned earlier, the Luton factory produced panel vans and a chassis/cowl form for fitting with specialist bodywork. There were, though, many other versions, and it was the availability of these which helped secure the CA’s market dominance. The Workabus was, as the name implies, a crew bus with wooden seats along each side, while the Utilabrake was a dual-purpose vehicle with a second row of forward-facing, padded seats behind the front ones, plus short, occasional-use wooden ones along the sides in the back. There were also pick-up trucks, ambulances, minibuses, mobile shops and much else.

Most of these were the work of Martin Walter, a long-established specialist coachbuilding concern in Kent and, though notionally independent, its conversions were fully approved by Bedford, sold through its dealerships, and the two names became intertwined in buyers’ minds, even though Martin Walter offered conversions based on all manufacturers 10-17cwt chassis that were commonly available.

However, it was their connection with Bedford that produced the overwhelming majority of Martin Walter’s output, and the number of CAs that passed through the Tile Kiln Lane works was enormous; it was, in many ways, like an extension of the Luton factory. In 1959 alone, over 10,000 CA-based conversions were made – that’s around 40 a day – and throughput was such that base vehicles for conversion arrived in Folkestone from the Luton factory by special train, with each ‘Dormobile Special’ carrying 100 vans.

The name Dormobile, incidentally, dates from 1957, when Martin Walter launched the first affordable camper van, based, naturally enough, on the CA chassis. Renamed the Bedford Romany in the early 1960s, the ‘Dormobile Camper’ was a development of an earlier, CA-based utility vehicle, featuring fold-down ‘Dormatic’ seats, and the option of laying flat to form a bed. From 1964, the Romany was joined by a second, CA-based camper, the distinctive Debonair, which matched the CA chassis/cowl with a distinctive glassfibre moulded body. It should also be pointed out here that, although Martin Walter’s Dormobile conversions are the best-known and most numerous, others – including Calthorpe, Kenex, Pegasus and Bedmobile – also produced CA-based motor caravans. These are often referred to – incorrectly – as Dormobiles, in much the same way as Hoover is used to describe any make of vacuum cleaner.

The Bedford CA today

Nowadays, these vans are highly sought-after; people love the classic and distinctive looks of a CA. Values have also risen dramatically in the past decade, a trend which, typically, started just after yours truly sold his Utilabrake in the mid-noughties! Nowadays, you’ll need five figures for a really good example of just about any version, and even a CA needing (very) complete restoration is unlikely to come for much under £2,000. Some versions – campers in particular – seem to be in fairly strong demand overseas, though export buyers tend to be both knowledgeable and choosy. They’ll pay well for a good example that’s been properly restored but, if it isn’t right, they probably won’t want it at any price.

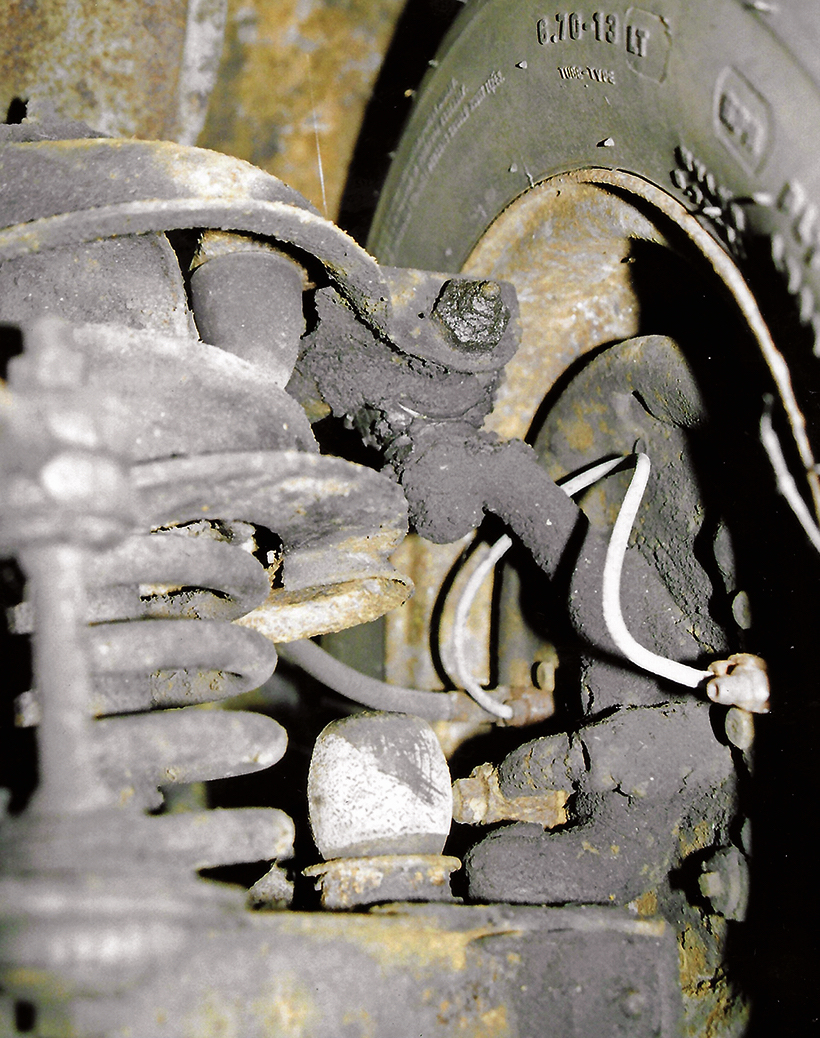

Despite being the most plentiful version when new, these days the plain CA van is the hardest variant to find; so much so that sometimes a down-at-heel camper will be converted back into van form! Needless to say, corrosion is the main issue; panel availability is patchy to put it mildly, but repair sections can be bought or formed for most of the common rot-spots, and the relatively simple body shape does make fitting replacement panelwork fairly straightforward, by restoration standards.

Trim parts (for early CAs, in particular) can be elusive. The best overall advice is to join one of the clubs catering for these vehicles – the Bedford Enthusiasts Club covers all Bedfords, and there are also camper- and CA-specific communities online.

For a money-saving subscription to Classic & Vintage Commercials magazine, simply click here