Mike Neale recounts the story of Ipswich Transport Museum’s 1951 Morrison Electricar GM 60cwt Coal Delivery Lorry and its renovation.

Austin Crompton Parkinson Electric Vehicles of Hall Green, Birmingham produced a range of battery electric vehicles with the brand name Morrison Electricar. The smallest was the BM 10cwt, then the CM 20cwt, the EM 40cwt and finally, the biggest in the range, the GM 60cwt.

The Co-operative Wholesale Society in Ipswich purchased a pair of the latter in 1951 to use for local coal deliveries, registered APV94 and APV95. Both, amazingly, remained in service until 1983, always retaining the red Co-Operative livery, rather than the newer turquoise and white colours adopted for Co-Op grocery vehicles in the 1960s. They were, however, extensively rebuilt during their working lives. Originally the bodywork had flat, faired-in side panels and more rectangular windscreens.

Ipswich Co-Op operated a fleet of around a dozen such vehicles after the war, based at their Derby Road depot, where coal was delivered by rail up until the early 1980s. After all, what better use for an electric vehicle than to deliver coal? Actually, it probably isn’t ideal, but more on that later.

After this Electricar was decommissioned, it sadly sat outside for six years, before being presented to Ipswich Transport Museum in 1989. A team of volunteers restored the bodywork, allowing it to be displayed in the museum.

It remained a static display piece, however. Fast-forward to 2016 and a team of museum volunteers had just completed the restoration of a Co-Op horsedrawn bakery van and were looking for a new project. It was decided to return the electric coal lorry to the road.

Work was split into two stages. The first was to restore the lorry to working order but without the batteries, for which a budget of £3,000 was anticipated. Then, once funds had been raised, phase two was to add batteries and a charger to allow it to be fully operational.

The team initially comprised volunteers Leo Brome, Dave Nelson, Dave French and Dai Jones. Maurice Charles then joined the team, followed by Doug Feveryear, with other assistance provided by Robert Fraser.

During the first phase, the wood was stripped off the body, retaining as many planks as possible, including several which looked beyond saving, but which Leo managed to resurrect. New wood was planed to the correct thickness by a company opposite the museum called Genesis which employs disabled people in woodwork tasks. This was done FOC in exchange for occasional use of the museum’s forklift truck. Bumpers and wings were removed and the frame taken off the chassis. The wings are made of rubber in the manner of some GPO vans of the period. The frame was placed on trestle tables and damaged sections repaired using new mahogany.

This allowed access to clean the chassis, remove any rust and repaint. The front brake pistons had seized in the cylinders, but Past Parts in Bury St. Edmunds blew the pistons out and serviced the cylinders, whilst new brake pipes were made by Pirtek in Ipswich.

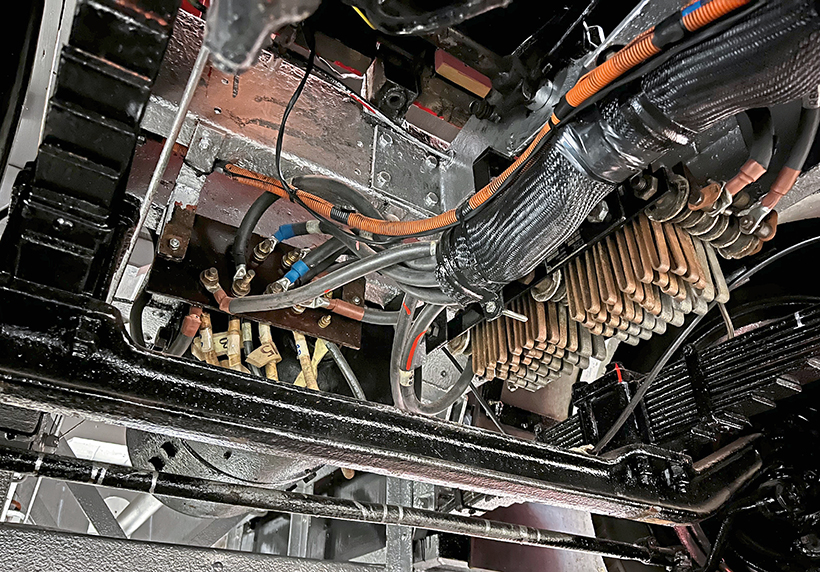

The propshaft was removed and repainted, whilst the diff was checked, cleaned and refilled with oil. The high current cables had to be replaced, as the insulation was dried, and crumbling conductors were blackened from overheating.

The resistor, consisting of many loops of steel and rated at 0.3 Ohms, was damaged from a partial meltdown where a lump of coal had got jammed between two of the loops when the lorry was in service. The solution was to weld a steel strap across the damaged area to bridge the gap, and when tested the loss of resistance was found to be negligible, so the original resistor was retained.

The charging socket interlock mechanism was missing so Leo designed and installed a new one. The electric motor was taken away for comprehensive tests by Boardly & Roberts of Great Blakenham. They rewound the armature, fitting new bearings and brushes and skimmed the commutator. The Electric Vehicle Company tested the motor, spinning up the wheels, first in forward and then reverse.

Meanwhile, Doug Feveryear refurbished the cab interior, renovating the seats and fittings. One half of the original split windscreen was cracked but was used as a template for a new one to be made by Car & Glass Trim. Finding new tyres in the right size of 7.00×20 was not easy but GW Tyres of Ipswich managed to track down two for the front wheels. The tyres are held onto the rim with a sprung locking ring, which if you aren’t careful when replacing can fly off across the room, never to be seen again.

Robert Fraser attended to the brakes, exterior lights, door handles and window winders.

Then lockdown came and work stopped. However, the team held fortnightly conference calls and a few elements were worked on at volunteers’ homes, for example Maurice Charles remade the price list board based on a 1970s photo.

The second phase of works was to acquire the forty 2V electric heavy-duty batteries and a charger.

To raise funds for this, a battery benefactor scheme was launched, members of the public donating £10 or more to have their name inside the lid of the battery box, as well as being issued a certificate, raising about £600 in total. Then in July 2018, the team was successful in being awarded a grant of £7000 from the Architectural Industrial Association for the motor rewind, high current cables, the remaining 2V batteries and the charger. The batteries are like those used in electric bikes and were made to order for this lorry by the Electric Vehicle Company, being installed in April 2022.

The original Morrison Electricar brochure indicates that it has a 12hp motor, roughly 9kW. The running current is around 100Amps. There is no regenerative braking, which you wouldn’t really expect on an electric vehicle of this age, although amazingly the museum’s 1916 Ransomes electric lorry does have this.

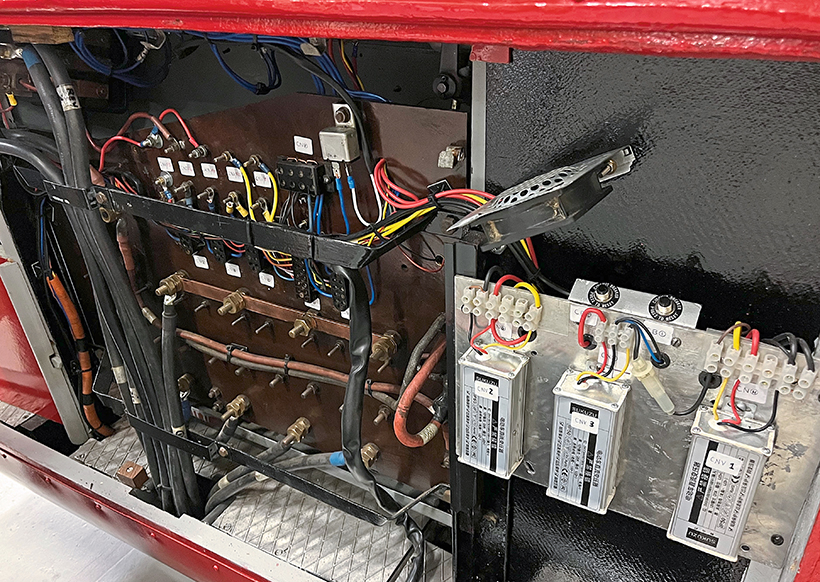

When depressed, the accelerator pedal operates five small contacts over 3.5 seconds, by allowing a spring powered piston to gradually rise and operate the switches in a sequence, which in turn operate larger switches capable of switching 100Amps.

The manufacturer’s operating and maintenance instructions for the lorry notes, “As soon as the vehicle is moving, keep the pedal right down. Use top speed even up the steepest hill, driving in a slower speed position does not save energy. Current is wasted in any speed except TOP.” Coasting downhill does, however, save current, although there is a warning not to exceed the maximum 25mph indicated on the warning plate to avoid damage to the motor armature.

Leo Brome told me about the driving experience.

“15mph is about its top speed on the flat, unladen, and more like 7mph going up a steep hill, so we added an amber flashing roof beacon for safety.”

“The controls are quite simple, with a selector for forward, neutral or reverse, an accelerator, footbrake and handbrake, but no gears, clutch or radiator. When it is in F or R, you cannot open the charging flap, and similarly if the flap is open you cannot engage F or R, to stop anyone accidentally driving off with it still plugged in.”

“The lorry needs to be unladen for us to be able to drive it on our licences. It just carries a few small coal sacks containing old beer cans, as ironically it needs to be non-flammable!”

“It has three modern converters to provide 12V for the lights, horn and wipers, with a 12V fan out of a computer to keep them cool. Originally the lights would have tapped into the first six batteries, but those would have got used up more quickly, and our new batteries are only guaranteed if they are all used equally, hence the need for the converter. We could have added a 12V battery, but then that would have needed to be charged separately.”

“We don’t yet know the range exactly, but reckon it is about 20 miles before it gets down to half power,” notes Leo. “A typical round for the Co-Op dropping off coal might have been around six miles. It’s not recommended to go much below half power, as fully draining the batteries would ruin them. At worst, you could perhaps go down to 20% if you then recharged them instantly. The deep cycle batteries should do around 2000 cycles in total, which we expect to last around eight years.”

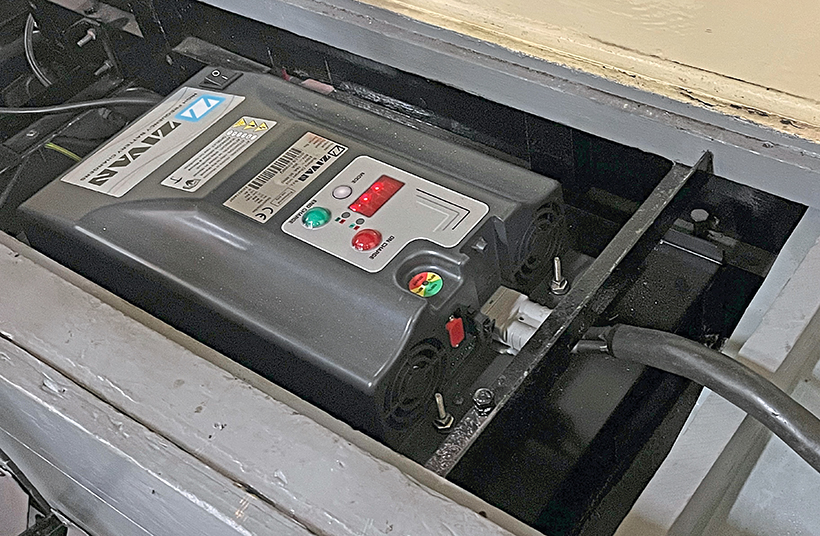

The museum has a 16A wall socket which connects to a modern single-phase charger hidden under the seats of the lorry. Solar panels have been installed on the museum’s roof to charge the lorry, taking around 10-12 hours to fully charge, or about five hours to top it up after use.

The restoration was a real team effort and required inventiveness by those involved both to get the vehicle working and in raising the necessary funds to do so. Professional help was brought in where required, particularly on safety related items.

The Wythall Transport Museum near Birmingham has some Morrison Electricar vehicles. The Ipswich Co-Op lorry is, however, believed to be the only surviving working example of the GM 60cwt lorry currently on the road.

With thanks to Leo Brome and Ipswich Transport Museum for their input to this article. See www.ipswichtransportmuseum.co.uk for information and opening times.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Classic & Vintage Commercials, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE