Peter Esposito explains the important role that the Ford Thames Trader played for London Transport from the late 1950s onwards.

I vividly remember my first sighting of the Ford Thames Trader sometime in the early spring of 1958, while using a Zebra crossing in the New Kent Road. Standing at the front of the stationary vehicles, a very smart and very different looking lorry was ticking over. It made a lasting impression on a young boy, as it seemed light years ahead of any other lorries on the road at the time – certainly compared to the offerings at my local British Road Services depot.

Having an interest both in lorries and London Transport (LT), I was pleased to read in the monthly LT house magazine of the decision to make the Trader the future standard chassis in its service vehicle fleet. What follows is a description of the events leading to this decision.

Often overlooked and perhaps surprising to some, was the fact that London Transport, from its inception in the early 1930s, through to its dismantling during the 1980s, was one of the largest operators of commercial vehicles in the UK. Over that period, there was a fleet of 5,000 miscellaneous vehicles, with 500 on the books at any one time; ranging from light vans to maximum capacity artics, with a whole wealth of specialised equipment in between.

These were required to assist with the everyday running of its vast transport undertaking, which included 10,000 buses and coaches, 4,500 Underground cars, 100 bus garages plus overhaul works, power generation plants, not forgetting canteens, staff uniforms and the publicity department.

London Transport became the first, fully-integrated transport operator in the world, responsible for providing a complex public service extending for a 30-mile radius of central London. Such was its esteem, that delegations from around the world studied LT’s structure, organisation and working practices when assessing whether this could be a blueprint for their own transportation industries.

On July 1st, 1933, government legislation created the ‘London Passenger Transport Board’, with responsibility not only for bus, trams and railways, but also for commercial vehicles and for the servicing and maintenance of the vast, complex enterprise. There had been much reluctance and campaigning from municipal boroughs and the private company shareholders, against what was seen as the compulsory purchasing of their assets, but to no avail.

The maintenance vehicle side of the operation was ill-equipped to fulfil its remit, with an inherited motley collection of vehicles, ranging from turn-of-the-century steam wagons, solid-tyred lorries, horse-drawn tower wagons, ambulances and fire appliances, to chauffeur-driven cars for senior management.

London Transport had been born in the middle of the great depression, with mass unemployment making funding to modernise the organisation difficult to attract. However, the government – just like ours today – decided to spend its way out of the economic doldrums that was crippling the nation, by providing guaranteed loans to various infrastructure projects, including the completion of the Queen Mary. London Transport secured enough funding to inaugurate the first and, alas, what proved also to be the last ‘New Works’ programme of 1935-40. Not only did this allow the commencement of a massive program of replacement of obsolescent passenger vehicles and the beginning of tramway abandonment but, passing almost un-noticed by the general public, the start of modernisation of the service vehicle fleet.

The London General Omnibus Company, which was the major contributor of motor buses to the new organisation, had previously preferred both the Morris van for 5-10 cwt capacity and Morris-Commercial from 1 ton to 30 cwt; a sound policy that LT continued. However, it was the middle-weight category that required the greatest attention. The answer came when it was decided to upgrade and expand the extremely successful GreenLine network in the late 1930s, by introducing high-specification AEC and Leyland coaches.

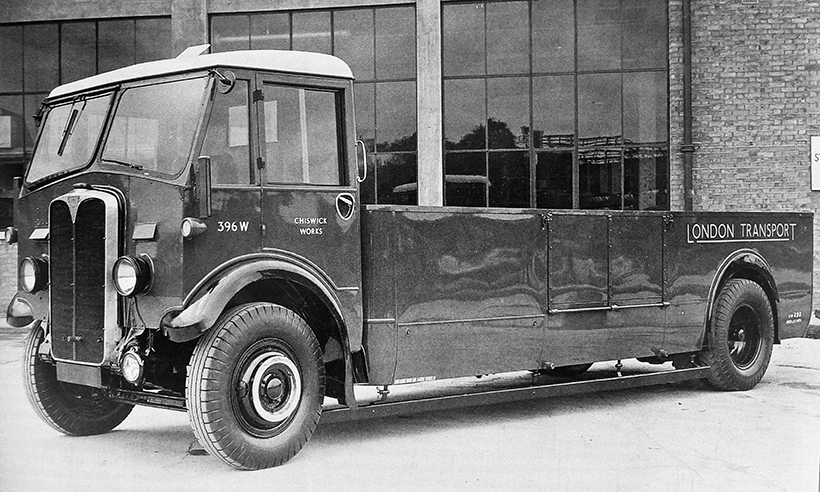

This released a large number of elderly, obsolescent AEC Regal coaches, the chassis of which were sound, but their lightly-constructed, timber-framed bodywork was assessed as being uneconomic to overhaul for further passenger use. Once again, LT decided to follow the path of the old General company policy of ‘recycling’, and 40 elderly Regal ex-passenger vehicles had their bodies scrapped and chassis overhauled. A full-width lorry-type cab and purpose-built body completed the conversion. This policy continued after the war, and another 40 buses were selected, but these were all of the double-deck type.

However, by 1956, the CDS (Central Distribution Services) had started questioning the economics of this buses-to-lorries policy. A former bus chassis has a high tare weight, therefore lower payload, long wheelbase and short rear overhang, which can easily overload the front axle, make steering heavy and put wear on front-end components. Compounding these shortcomings, road taxation at the time was based on unladen weight, making the Regals even more disadvantaged, compared with a purpose-built lorry.

By this time, LT had centralised the servicing of these AEC Regal conversions in the former bus garage at Nunhead in Peckham – a premises that, in turn, would be leased to Charles W Banfield to stable his ever-growing coach fleet. LT accountants, discovering the cost of maintenance and time spent off-road, sometimes up to six weeks, thanks to sourcing spares for 20-year-old vehicles, the conversion policy was abruptly dropped.

Only new, medium-weight ‘off the shelf’ lorries would be purchased with the benefits of less maintenance, readily available spares and warrantees from service agents. Although 12 handsome AEC Mercury vehicles were the first new arrivals in 1957, these were for a particular job; helping to dismantle LT’s huge trolleybus system, and weren’t considered for the new standard, middle-weight stores carrier. A cheaper, mass produced vehicle was required.

Bedfords were considered, but the ‘S’ Type was approaching its eighth birthday and would probably be replaced in the near future, so the standardisation that LT craved wouldn’t be possible. The Luton manufacturer had been successful in the late 1940s with its war-proven ‘O’ 5-tonners and ‘KD’ 30 cwt models, both being added to the LT fleet, with the latter proving a particularly successful bus garage runabout. A new forward/semi-forward control design, with at least a six-to-eight-year production life ahead of it was needed.

Meanwhile, Ford had been working on a project of entering the middle-weight market, and the company’s first thoughts were to morph the current ET normal control model into a semi-forward layout. Using the existing ET Briggs cab as a basis, various mock-ups were constructed, leading to road-going prototypes, with the code name ’Atlantic’ – probably because the management thinking was all at sea! Luckily, seeing the error of their ways, they quietly dropped this ‘ugly duckling’ and a completely new tack was pursued.

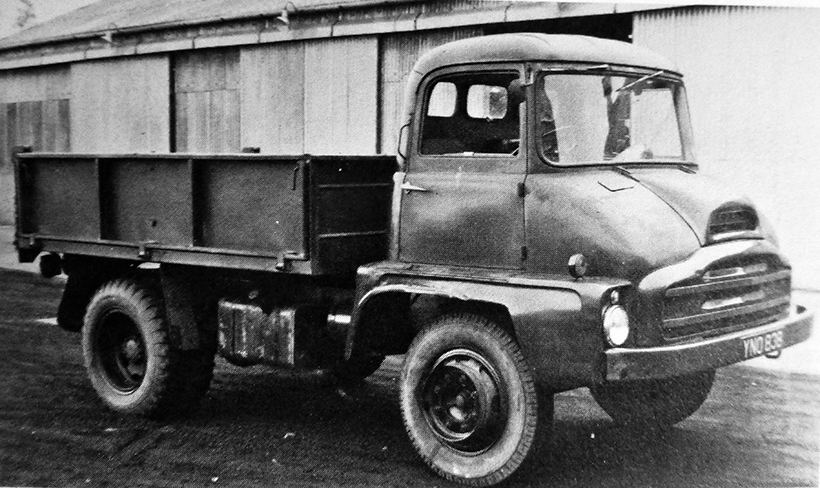

The resulting Ford Thames Trader, which was launched in 1957, provided LT’s answer to the middle-weight carrier requirement problem. It not only ticked all the right technical boxes, but was also built within LT’s operational area on the Thames, at Dagenham – loyalty to UK manufacturers, how quaint! The Trader was quite radical, its crisp angular design certainly marking it out from the opposition. Unlike the Bedford ‘S’ Type, which took its styling cues from the US, the new Trader had a more European look from the design studios of Ford UK and Ford Cologne, Germany.

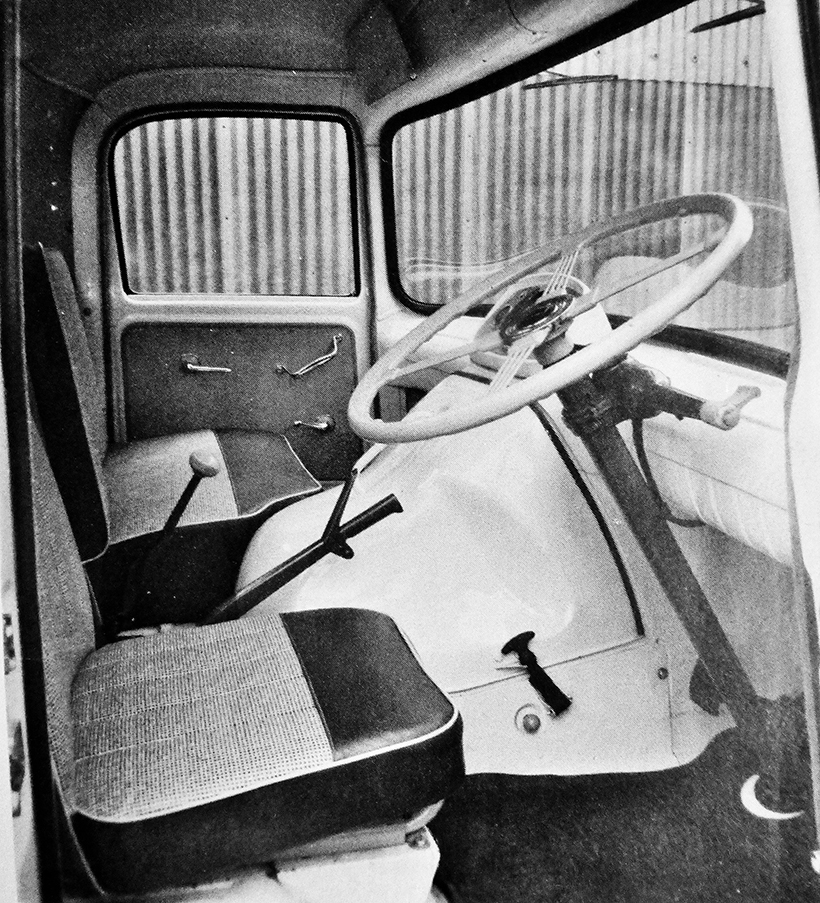

The introduction of this lorry was extremely important to Ford as, for the first time, it would take the company into the 11-ton bracket, a very competitive sector, not only with other mass-produced types, but also with the premium brands. Getting it wrong would have damaged Ford’s reputation. The Vauxhall management had experienced this to their cost with the 1961 Victor and that rust problem. With this in mind, the designers had to get it right first time, and had been fine-tuning every detail, until the definitive version emerged. The Trader marked the return to the semi-forward control layout (shades of the old 7V?) with a short protruding snout helping to lessen engine intrusion into the cab.

Cab entry was difficult but, once aboard, drivers found controls well-placed and forward vision extremely good thanks to a one-piece screen and short, sloping bonnet. Ford described the cab as ‘slim and snug’ but a more honest assessment would have categorised it as cramped! Although not perfect, it certainly made the Big Bedford look dated, resulting in Ford capturing a very large slice of the middle-weight market, with the advantage swinging back in Dagenham’s favour.

The Trader 500E was initially offered from 30 cwt up to 7 tons, with two diesel and two petrol engines and three wheelbases, 108in, 118in and 138in; a model line-up to satisfy most operators’ requirements.

London Transport received its first two Traders in September 1959 and, over the next six-and-a-half years, took 140 into stock, fitted with standard and specialised bodywork. Open, semi-open, covered, towing, crew-cab (no laughing, please!), and box-bodied versions with payloads of 3, 5 and 7 tons, plus articulate units at a later date. The earlier deliveries were in the traditional ‘Chiswick Green’ livery, but this soon changed to ‘Cargo Grey’, which was the standard Ford finish. Ford would not supply the Traders in primer, so it was decided to keep the high-class factory enamel livery, and not repaint in traditional green.

When LT required a small number of long wheelbase Traders not listed by Ford, a vehicle would be dispatched to Baico Ltd, a firm specialising in extending chassis frames. Also, when previously a gang of men were sent out on a job, most of them were carried on the load bed of the lorry; a practice quite acceptable in pre-Health & Safety days.

But, when rules were tightened, a crew-cab was needed, with the firm of Reliant reputedly given the contract for grafting an extension to the ‘slim’ Trader cab. Studying photographs shows the extra row of seats were only accessed from a second door on the nearside, necessitating an uncomfortable scramble. This ‘un-ergonomic’ layout was further compromised by the absence of an offside window. All these features were at the insistence of LT’s chief medical officer – I wonder if one of his offspring went on to become a member of SAGE?

For a money-saving subscription to Vintage Roadscene magazine, simply click here