Bob Tuck explains the interesting evolution of car transporters from the 1960s; the ear in which car sales began to boom.

Photographs: Ken Glendinning collection

The evolution of car transporters in the UK is an interesting story. The first examples in the UK appeared about 1948, and their subsequent growth during the ‘50s was generally in operators based close to the car-building factories which, in the main, were either at Dagenham (Ford) Luton (Vauxhall) or the triangle linking Birmingham, Cowley (Oxford) and Coventry. However, as well as a small number of country-wide dealers/garages which ran their own outfits, there was a growing band of out-based general hauliers that dipped their toe into the car transportation.

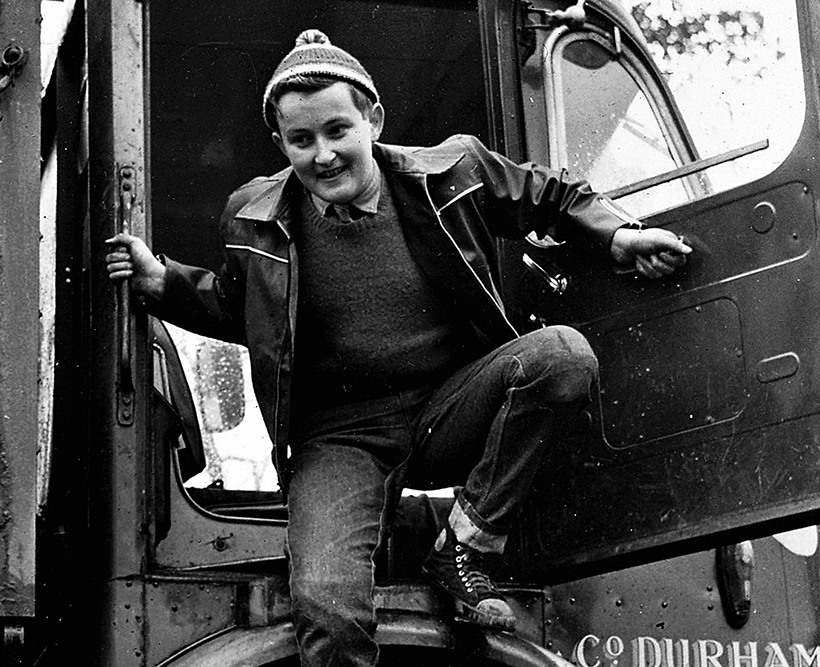

In the North East of England, it was to be WA (Archie) Glendinning that made such a move in 1960, when the BMC – Taskers – Burtonwood artic SJR 100 (driven by John Thompson) began running a lone furrow up and down the country, bringing an assortment of brand new cars/vans back at first to Consett – and then into the Buist (Morris) dealership at Newcastle. It was Archie’s eldest son, Ken, who travelled with John as often as schooling allowed. While he later went on to serve an apprenticeship in the garage at Consett Iron Company, it was this early time he spent learning the ropes in the car-moving game that perhaps proved just as important.

First stop. Mrs Green’s

Ken has lots of vivid memories of those days in SJR 100, first as a passenger and then, once his age allowed, as its driver. Doing three return trips a week from Shotley as the norm (covering about 1,600 miles) meant the pedal was always down and, while you could generally make decent progress – with 50% of the running time being empty – Ken recalls how SJR could be a hairy ride: “With the big tail lift being right at the back,” he says, “it was a bit like the tail wagging the dog.”

Ken obviously got used to that distinctive trailer swing, and he also got used to calling in at Mrs Green’s transport café at Brotherton, just north of Ferrybridge, after the first 100 miles from base had been covered: “It was a regular first stop for years either going down for breakfast, or coming back up for dinner. Although it was originally just a converted railway carriage, the site then became Norman’s Café and, while the car park could then be a bit iffy with the potholes, they also had beds there. I remember going in there a lot with John and, after the meal, one of the women would always give me an orange – she must have thought I needed feeding-up.”

In the early ‘60s, the way to Oxford and back followed the same path, although it was a huge, time-saving boon when, in 1961, the Doncaster by-pass was opened. Many sections of the A1 were gradually being ‘dualled’ (apart from that odd, short stretch that ran through the old county of Rutland) but, the Glendinning artic would leave the A1 near Clumber Park, and head south for Leicester – via the A614 and then down on to the A46 – before heading for Rugby.

If you had to collect from Luton, you could jump on what was the northern end of the new M1 motorway (at Crick), and wind the motor up. But reaching the Morris factory at Cowley was still a rural meander via Dunchurch, Southam and Banbury. Ken could probably drive this route in his sleep, but one thing he also recalls about the Morris factory is how, at first, it wasn’t really geared-up for receiving car transporters: “The operation had been built to dispatch new vehicles, one at a time, driven by platers,” he explains, “so, at first, we had to park on a nearby trading estate and ferry our load of cars (one at a time) back to the wagon. I used to help John driving them in the plant, until they realised I was under age and then I was barred – but just from driving in the factory!”

It was a huge boon for the growing number of Glendinning transporter drivers that, as traffic increased, Archie was able to open up his own transit yard just north of Oxford, at Kidlington (behind Bob’s Café), and the staff based there shuttled the new vehicles out from the plant. While in 1964, Archie even found a job for yours truly – and paid me £9 a week for my troubles.

Double your money

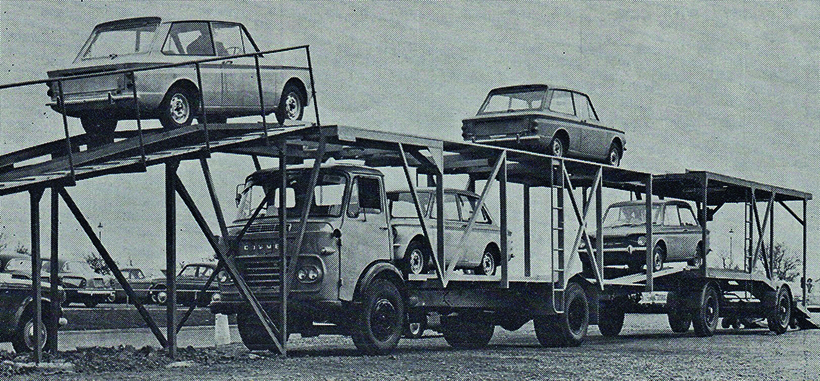

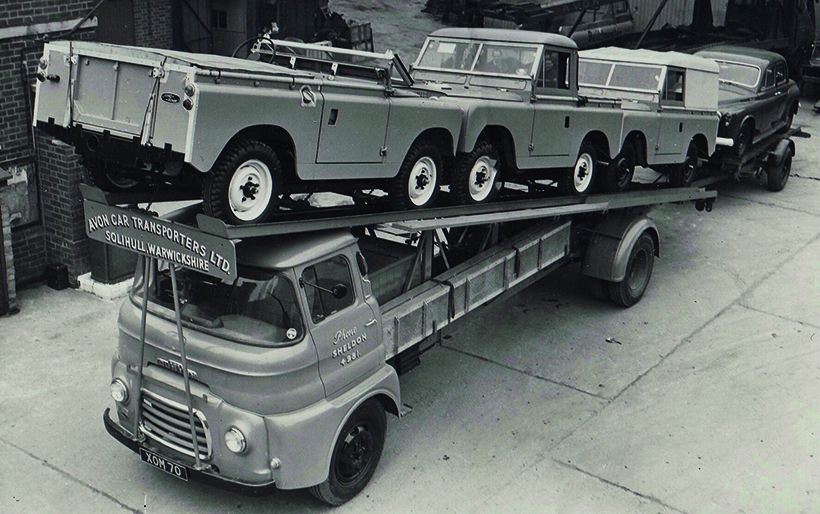

It always struck me as odd that the industry was slow to make the shift from artics to ‘wagon and drags’. Being able to run at almost double the length meant they could be relied on to carry possibly double the number of cars – and so probably double their amount of bottom-line revenue. The first such outfit in the UK that I’ve heard was the four-wheel Leyland Beaver and trailer that Rover put into service during June 1951.

It was used, in the main, to run new Land Rovers down to a variety of different docks for export. With the body built by Brockhouse, it had a hydraulically-operated deck on the Beaver, but a fixed top deck on the trailer, so loading the top deck of the trailer (with fairly high Land Rovers) saw the wagon and trailer butt up to each other, so the two vehicles could be individually driven over – from top-to-top. Yes, you certainly needed a good head for heights if you were involved in the transporter game!

I have to presume this outfit did its job well, although there were one or two downsides to its operation. It obviously needed a lot more space to load/unload and, traditionally, it had a speed limit which was 10mph slower than artics. So, when most motors had their speed limit raised to 30mph, the drags were still stuck at 20mph. And when that was eased up again to 40mph, the wagon and drag was stuck at 30mph – honest. And Ken can testify to being stopped one day in Kent by the law – but just cautioned – for such transgression.

Another part of the law at the time relating to the drawbar outfits was the need for a driver’s mate – or ‘statutory attendant’ as they were called. In this first, Rover outfit, as well as helping with loading, the mate’s long-time duty was to operate the trailer brake. This was a multi-pull ratchet lever which was fitted in the nearside of the cab, in front of the mate’s seat. Pulling the lever (multiple times) tightened the wire that ran down the outfit to the trailer brakes. This was never a totally satisfactory system (depending on how it was maintained), but it certainly beat the prior arrangement where a mate had to jump down and run alongside the trailer to try and apply the mechanical handbrake that way!

Another wagon and drag I know from this early era was the similar Leyland – SJY 545 – operated by the Plymouth Transport Co, which was emblazoned with ‘We can do this for you’ down the side. It was also a four-wheeler, but the company had actually specified a Leyland Steer (six-wheeler) but with the second steer removed to ensure a much longer chassis. Built by Carrimore, both the rigid and trailer were fitted with hydraulically-moving decks.

In fairness, during the ‘50s, the industry was just getting used to the gradual development of artics, but what blew the door open for the wagon and drag to take its true place was a combination of several factors. The arrival, in 1959, of the motorway age (where, at first, there were no speed limits, for anyone) meant the drags could run free, while Leyland came up with just the high-flying steed (its Super Comet) for such an application. It was a real goer!

While, of course, the emergence of Alistair Carter into the mix brought the tastiest of visions to the fore.

The Carter dozen

It was in 1964 that I was offered the role of driver’s mate on CJR 320B – the brand new Leyland Super Comet and Carrimore trailer that Archie had just put into service. I’d just left school and, at the time, had a casual driving job with the Consett branch of the Co-op (CWS). But I leapt at the chance to go long-distance with Dennis Williamson, as its regular driver. Strangely, there was no hand brake for me to operate in the cab (it had been done away with as, by then, the air brakes of the footbrake were all piped through to the trailer), but the legal need for a trailer mate was still in force.

For the next 18 months or so, we went all over the country (normally) bringing new motors back to the north east. I say ‘normally’ because I recall regularly going to Newport, in South Wales, to collect ex-hire cars that had been shipped in from Jersey en-route to their new owner – The Cowie Group, of Sunderland.

I also have happy memories of doing some day-runs to collect Vivas from Vauxhall’s new factory at Ellesmere Port, that took us (empty) over the tops via Stanhope. We came back loaded via Skipton, although we then routed ourselves via Otley, to avoid the daunting climb up Blubberhouses on the A59, near Harrogate. Dennis would normally run out of hours before we got back home but, often, another crew would meet us at say Londonderry or Scotch Corner and, after swopping over, I would drive us back to the garage in Archie’s brand new Mini Countryman. That was always a pleasure!

They were great days, but our normal (three times a week) bread run was from Shotley Bridge to Kidlington, for a load of nine cars for Buists in Newcastle – with the regular overnight stay at the ‘Drome’, near Leicester. This was nearly double what the Glendinning artics were picking up, but we were usually two shy of what Overland (from Carlisle) was putting on to its Super Comet and drag, from the compound next to us. The reason, of course, was that its 11-car carrier was a lot longer than ours, as it was built by Tamworth manufacturer, Alastair Carter, who read the Construction & Use length regulations in his own way. He went to court many times to defend his customers, and always won his argument.

There were other differences between the Carter and Carrimore outfits. The Carrimore could be loaded a lot quicker – as the top deck of the wagon was operated by hydraulics – because the Carter outfit used an electrically-driven lift to individually raise each of the cars to the upper deck. But, if you thought getting 11 cars on was good (provided there was a strong sprinkling of Minis in there), Alastair went one better and built outfits which could actually carry 12.

Although a regular ‘New Year Wish’ for the car transporting industry was the hope of being allowed an increase on the overall length of artics, it was when the width of a heavy was increased to 8ft 2.5in, that Alastair got excited. As he reckoned he could then squeeze a 12th car (a Mini or Hillman Imp) alongside the driver and mate, provided they sat one behind the other. While, of course, that’s provided the super structure was built on a coach chassis which had an under-floor engine. What a great wheeze.

In fairness, these half cabs weren’t the nicest of motors to ride in as Ken can still recall: “I was down at Kidlington when I got a call that I had to urgently collect – on trade plates – a Renault at Southampton. I went across to Bob’s café, looking for someone to give me a lift and, fortunately, there was a transporter from A&C McLennan of Perth, that was going there, and offered me a ride. That motor was a half cab – on a Commer bus chassis – but as it was only pulling a small pup trailer (that could only carry two cars), a mate wasn’t needed so there was room for me, although I had to put the driver’s overnight case on my knees. There was very little room in that cab, and it was really very basic.”

The bubble bursts

We featured the life story of the late Alastair Carter back in the July ’15 issue of Heritage Commercials. But it would be remiss of me not to mention (at a time when they are very much in vogue) how in 1967 he appeared before the United States Senate to talk about the bringing into use of electric vehicles. Yes, he was a man ahead of his time in many respects, although he was brought back to earth when the UK legislators changed the wording of the law to make it illegal to utilise the front and rear extensions that many in the industry had got used to. Ken recalls that this ruling also hit the Carrimores, which reduced its ‘normal’ capacity to eight. So, as an option (that meant the mate hadn’t to be employed) a two-car ‘pup’ trailer was often used in place of the four-car one, so a load of seven cars became standard.

In the late 1960s, once he’d reached 21, Ken took over this hard-worked Super Comet when regular driver Dennis decided to emigrate to Australia. I’d left in late ’65 to join the police, and it was Peter Hillary who took over the mate’s seat as and when the big trailer was pulled.

Although the Carter drags had lost their sparkle, Alastair was to turn his attention to the artic market and, as time progressed, the law-makers gradually relaxed the overall length maximum all the way to 15 metres. These new Carter semis may have been light, but there was plenty of competition and, while Brockhouse had quietly left the scene, Carrimore were going from strength to strength. Ken has always been impressed with the SACO semi-trailers made by Hoynor, in Essex: “These ‘Single Axle Cars Only’ were a bit ‘cheap and cheerful’ but they suited a lot of operators.”

One operator who built his own car carrying semis in the ‘60s was Kirkcaldy-based Doug Harvey, and Archie bought one from him to run with a rather special TK Bedford tractor unit on contract to the north-east Vauxhall dealer, Adams & Gibbon. “The Harvey trailers were on the light side,” recalls Ken. “We eventually had three of them – the original one; the longer version when the C&U lengths changed, and a second-hand one from Barclay Bros, Fife. I remember driving the Bedford on its first week. Doug Harvey did the first trip with me, but I managed to boil the grease out of the rear hubs as that TK could certainly shift. We obviously then fitted the right grade of grease and it wasn’t a problem!”

For a money-saving subscription to Heritage Commercials, simply click here