With period photographs and reports from John Wakely, Alan Barnes reflects on an impressive engineering achievement; building the M25 motorway

John Wakely once commented: “I think it’s a wonderful road and, if you didn’t have it, could you imagine?” He was referring to the building of the M25 motorway but now, nearly 35 years later, I’m guessing that few might use the word ‘wonderful’ to describe the London’s orbital motorway.

I’ve you’ve been stuck for hours in stationary traffic on what can sometimes amount to a four-lane car park, I’m sure that most of your impressions would be unprintable here! Nevertheless, John’s appreciation for the overall usefulness and convenience of the M25 is completely understandable, as is his enthusiasm for the scale of the project, and the degree of engineering expertise involved in completing it. What’s more, at least the parking is free!

Timely site access

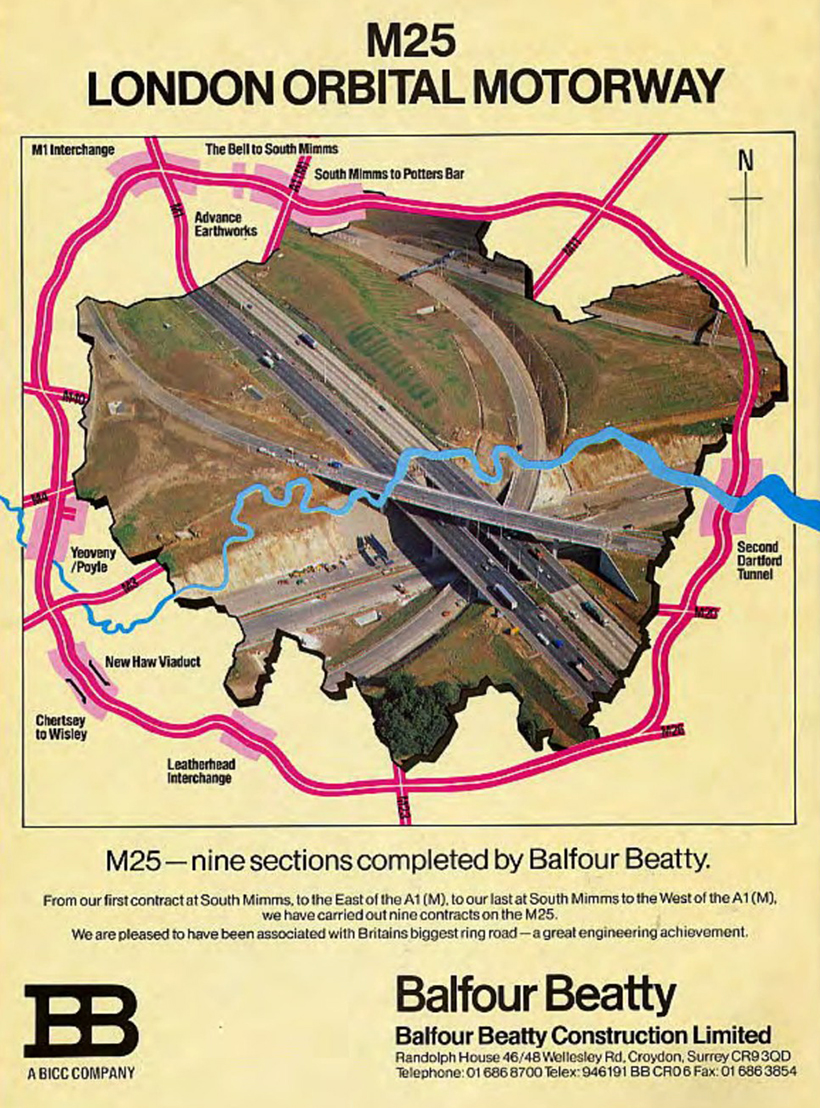

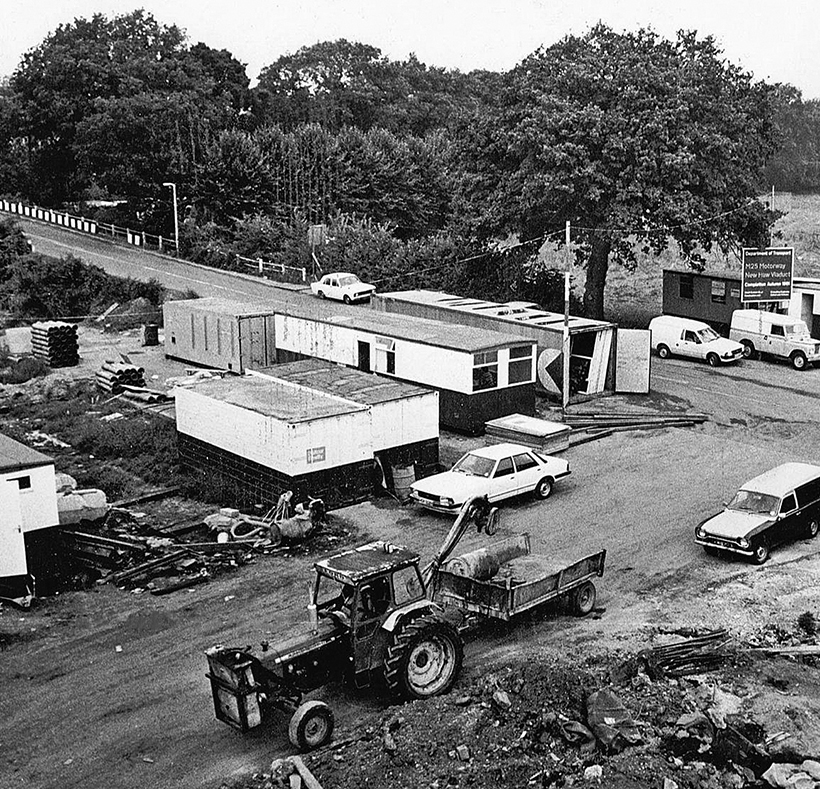

In 1982, some four years before the motorway was officially opened, John took the opportunity to photograph some aspects of the construction work being carried out at Wisley, in Surrey. This would eventually become Junction 10 – the interchange with the A3. The contractor on this particular section was Balfour Beatty; one of the main ones on the project, and the firm responsible for building the first and last sections of the 117-mile motorway.

John’s photographs recall the impact the construction work had on this part of Surrey, with fields and woodland being decimated as the road cut through the countryside. However, nature is very resilient and, today, the woodland has recovered and the once bare, sandy embankments are now covered with trees and wild flowers.

His access to the site was hardly ‘official’, but the contractors looked after him and even let him drive one of the Terex dump trucks being used on the site; certainly not something that would be allowed on a construction site today!

The concept of an arterial ring road around London was by no means new, having been raised by William Rees Jeffreys in 1905, when he informed the Royal Commission on London Transport that it was a disgrace that there was no road which encircled the English capital. The eventual outcomes were the development of the North Circular road, which was completed in 1930, followed by the South Circular road, finished towards the end of the 1930s.

War halts plans

In 1937, proposals for a new orbital route were included in the Highways Development Survey, prepared by engineer Sir Charles Herbert Bressey and the famous architect, Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens. However, the development and implementation of these plans was halted by the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1944, the Greater London Plan included details of five ring roads around the capital, intended to cope with the increasing traffic – with the existing North and South Circular roads being the middle road of the five planned routes.

Plans drawn up in 1965, after the formation of the Greater London Council, reduced the number of routes to four, but these plans were eventually abandoned in 1973. By this time, construction work had begun on smaller stretches of new motorways, designed to link up with existing major routes. These included the M16, which linked the M1 with the Dartford Tunnel and opened in 1963 and, south of the Thames, a new motorway – designated the M25 – that was built to relieve traffic on the heavily-used A25.

In 1975, the Minister of Transport, John William Gilbert, made the announcement that the existing M16 and M25 would be extended to form a new orbital motorway, the M25. However, the news was greeted with dismay by groups and residents of the areas which would be affected. During the consultation process, 39 pubic inquiries were held and there were more than 700 days of hearings.

Bite-sized chunks

Construction of the new orbital motorway would be in stages, with most of the country’s leading civil engineering companies being involved in the work, together with hundreds of sub-contractors. The main firms on the project included Laing, Costain, Bovis, Fairclough, McAlpine, Tarmac, Birse, Wimpey and Gleeson.

Balfour Beatty was awarded the contract for the first section, to be built between what’s now Junction 23 and 24 – South Mimms to Potters Bar. This part of the project was opened for traffic in September 1975. Balfour Beatty was also responsible for the completion of the final part of the M25, the section between Junctions 19 and 23, which was opened in October 1986.

This company also handled the work on the stretch between Wisley and Chertsey – Junctions 10 to 11 – which presented problems of its own as the motorway had to cross the River Wey Navigation and a main railway line. The canal and railway were spanned by the 310-yard-long New Haw Viaduct, and this part of the motorway was opened in 1983. Looking at John’s photographs, taken in the summer of 1982, it seems hard to accept that just over a year later, the motorway along this stretch would be open to traffic.

The work along the Wisley section started in September 1981, and involved the excavation of an estimated 22 million cubic feet of sand, which John recalled as giving the site the appearance of a gigantic layer cake, with alternating pure white and bright orange sand layers making achieving the correct exposure with his Pentax camera, something of a nightmare!

Construction at Wisley

As John recalled: “This series of photographs was taken on the M25 construction site at Wisley (Junction 10) in July, 1982, where the main A3 crosses the M25. Some of the negatives were very hard to scan due to exposure problems with the wide open space.

The road bridge construction can be seen, together with some cracking shots of the Terex earth-movers. They had 57 of them on the M25 at the peak time. I owe thanks to the hard-working guys and Balfour Beatty, for allowing me to be a total nuisance while taking these pictures. It's a wonder I'm not buried underneath it. Seriously, though, they were very patient and took quite a few prints home with them to show their grand-kids. Great work lads!”

As well as photographing the excavation work and the fleet of Terex dump trucks at the site, John also captured some of the huge fleet of ancillary support vehicles which he found on the approach roads leading to the site. These ranged from County tractors and Bedford and Leyland water bowsers, to Foden tippers.

John noted that there was one guy who drove a Bedford TK which was loaded with barrels of grease. His job was to drive around the site all day, greasing the Terex dump trucks and, as soon as he’d finished the whole fleet, he simply started again at the beginning.

Coming across Bedford and Foden lorries wasn’t unusual on a UK construction site in those days but, from time to time, John would encounter one or two ‘oddities’. These included a French-built Berliet six-wheel tipper, which was part of the Dobson fleet; presumably one of the sub-contractors involved in the project. Another ‘foreigner’ was the Magirus Deutz 232 six-wheeled fuel tanker operated by Dalton. It seemed well able to deal with the rugged, off-site conditions.

Promotional brochure

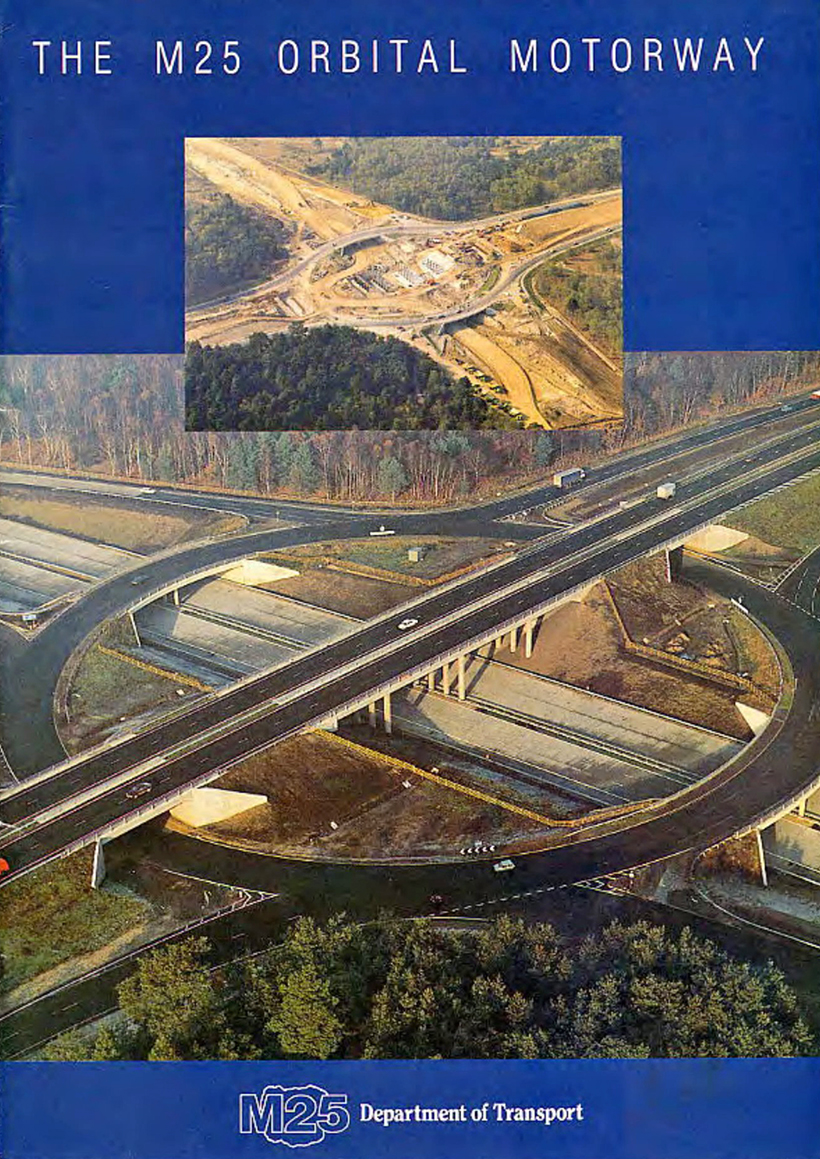

The Ministry of Transport issued a brochure on the new motorway, which included a foreword from the Secretary of State for Transport, which stated: The M25 London Orbital Motorway is the longest city bypass in the world – 117 miles of communications vital to Britain’s economy, and to improving the quality of life in the capital and towns and villages previously clogged with traffic.

The achievements involved are vast. Remarkable feats of civil engineering are combined with a real concern for the environment, and the overwhelming need to improve peoples’ daily life. The M25 is more than an impressive road. It is a testimonial to British expertise, not just in engineering but in successfully matching the demands of commerce and industry, with those of leisure and local communities. The road’s completion serves to remind the nation and the world that Great Britain is a leader in design, construction, innovation and environmental improvement.

However, the motorway has been a victim of its own success and over the past 30 years, and various sections have been upgraded. The stretch between Wisley and Chertsey is notorious for lengthy delays, despite the building of additional lanes, and there are plans for the A3 interchange at Junction 10 to be rebuilt. If that work goes ahead, it seems unlikely that any of today’s amateur photographers will be allowed the access to the sites that John enjoyed, nearly 40 years ago.

With thanks

Archive photographs and information from John Wakely, together with information from Get Surrey, is gratefully acknowledged.

To buy a money-saving subscription to any of Kelsey Publishing's fascinating, transport-related magazines, simply click here