Peter Simpson revisits the father-and-son Fitch team, who have just completed another fine Bedford restoration that reflects the family’s history with lorries.

Exactly two years ago, in the September 2018 issue of Classic & Vintage Commercials, we featured Alvar and Garry Fitch’s newly restored 1958 Bedford D. In that feature, we mentioned that the D was “one of three Bedford restorations nearing completion.” Now, though, number two has been completed. It’s a 1936 WT three-tonner, like the D, it’s absolutely stunning, and we were therefore delighted when the invitation came to take a look.

Also like the D, the WT is a lorry type which the family intended to use operationally, but never did. To explain this, we need to start with a brief look at the family’s background in lorries and road haulage. This started in the 1920s, when Garry’s grandfather, HB Fitch, established a coal and coke merchants business in Cheshire with, as was usual then, a horse and cart.

From this, he graduated to a Model T Ford and then, in 1932 ,the Fitch’s first Bedford; a 1932 two-tonner. Then, in 1938, he ordered a new Bedford three-tonner from Salthouses, the Bedford dealership in Ashton Under Lyne. However, it took until 1939 for the order to be processed, by which time, war was looking increasingly likely, so he cancelled the order. He continued using the old lorry until he was called up, at which point his wife (and Garry’s grandmother) took over.

Consequently, the WT has been restored to replicate, as far as possible, what the ‘new’ lorry would have looked like, had it arrived in 1938/9, as intended. In this, they’ve been guided by the livery and finish of both the 1932 lorry and the O-Types, J-Types and TKs that the Fitch business operated post-war. The one thing that isn’t certain, however, is whether a new three-tonner in 1938/39, would have been the older model as represented here, or the new- in-1939 ‘Interim’ model. with the bull-nose front.

Long-distance restoration

At this point, we also need to reiterate a little about how this father-and-son team carry out their restorations. The first complication is that the pair live some 200 miles apart – Alvar’s based near Manchester while Garry, who works ‘in finance’, lives on the western edge of London, near Heathrow Airport. All their restoration work is, however, done at Alvar’s premises, meaning a 400-mile round trip for Garry for each joint working session.

Secondly, whereas most people with several lorries to restore, would tackle them one at a time, the Fitches have chosen to run three simultaneously. This approach, though unconventional and requiring a fair bit of planning and self-discipline, does have one big advantage when, as here, you’re dealing with rare vehicles. You can work when parts are available and then, rather than doing nothing while waiting for scarce spares to materialise, you can switch attention to one of the other vehicles.

This is why, on paper, this restoration took 19 years between acquisition in 2000, and completion in 2019. For most of this time, it was one of three lorries being restored simultaneously. It was not worked on continuously, and there were significant gaps while waiting for parts and/or where one of the others was being given priority for another reason. As already noted, the D Type which had been started in 1997, was finished in 2018. The third long-termer, a 1952 O Type, has yet to appear though, apparently, it’s been completed to ‘cab and rolling chassis’ stage.

New in Norfolk

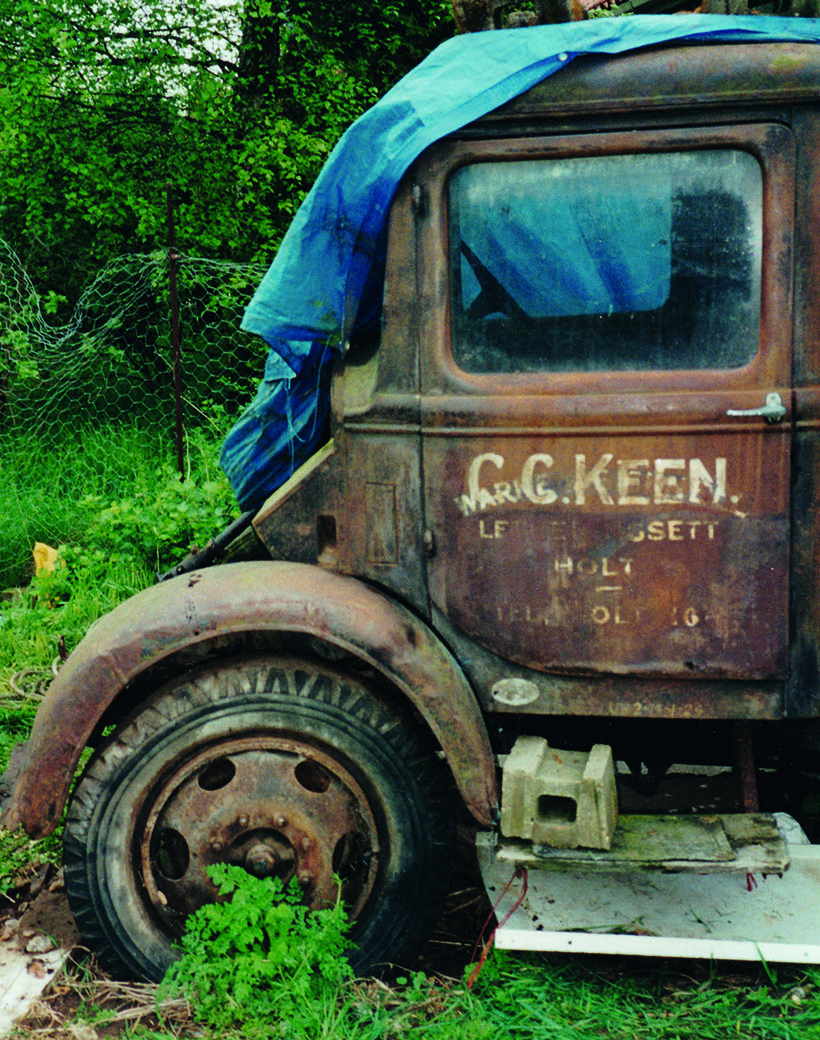

The WT that the Fitches restored was new – or possibly nearly new – in 1936/7 to Warne & Bicknell, which was a ‘steam haulage contactor and general carrier’ based in Letheringsett, near Holt, in North Norfolk. It was supplied by a dealership named Carno, and needed as a replacement vehicle following a fire at Warne & Bicknell’s premises in early 1936. That fire destroyed two vehicles. Almost immediately, however, Warne & Bicknell decided on a change of direction, with the haulage side – and the WT – passing to an employee named Colin Keen.

Keen ran the WT on his own account until 1949 when, for reasons unknown, it was placed in a barn locally. There it remained for 46 years until, with the farm premises needing to be cleared for sale, it was sold at auction in a sale which attracted a not-inconsiderable amount of local publicity. The buyer was a local blacksmith who intended a full restoration, and spent the next five years getting together some spare parts to assist with same. Little if any work was completed, though, and the WT was left sheeted-up. In 2000, it was sold again in pretty-much unchanged condition.

The buyers, however, weren’t Alvar and Garry; rather it was bought by Garry alone. The pair had inspected the lorry with a view to a joint purchase but, while Garry was happy to go ahead, Alvar felt it was too far gone. So, Garry decided to buy it on his own, and the lorry, along with the spares, were transported back to Manchester. Then, as work started, Alvar came round, realised it wasn’t actually as bad as he’d feared, and agreed to go 50/50 with Garry.

Lots to do…

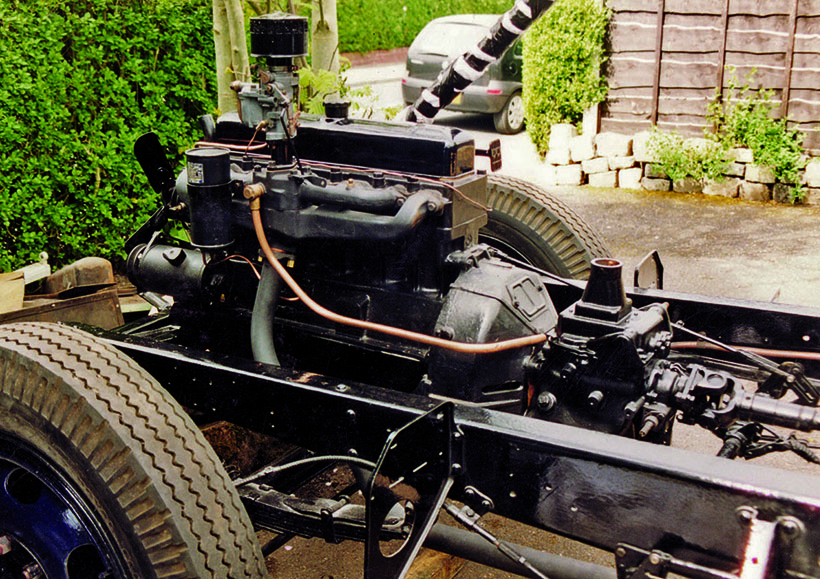

Having said that, though, there was still a massive amount of work to do, with the mechanical condition as bad as the bodywork. The main issue mechanically was that the engine block had cracked and, while this had been repaired, Alvar and Garry both felt that building a ‘new’ engine around a repaired block was unwise. The team had acquired a number of mechanical parts, such as pistons and bearings.

They also knew of a very rough SWB WT that was sitting in a Sheffield scrapyard, and bought that as a donor vehicle with the intention of using the engine block from that. Unfortunately, however, that one turned out to be full of water, and completely unusable, though the donor vehicle was still extremely useful and ‘donated’ many other parts, including wheels, some springs and a front axle assembly.

At this stage, we need to mention another unusual aspect of these father-and-son restorations; they tend to be punctuated, every so often, by ‘friendly disagreements’ over aspects of the work, and it’s not unknown for one to play a slight trick on the other. What followed was a classic example of the latter. While Garry was pondering and worrying a bit about how to source an engine block, Alvar calmly suggested ‘we’d better use that reconditioned unit I’ve had in the back of the shed for 40 years…’ In his own words Garry ‘hit the roof’, but was, of course, relieved and delighted that such an easy solution was possible.

You need friends

As noted earlier, finding parts did present one or two issues although, having been around lorries and the preservation scene for many years, Alvar and Garry have many contacts – and their contacts have contacts – and, as time went on, a lot of rare stuff was sourced. This included panelwork such as wings, a front bumper, bonnet top and a radiator grille/shell, while the fabulous and much-missed classic car spares emporium at West Drayton, had a replacement window winder mechanism on the shelf.

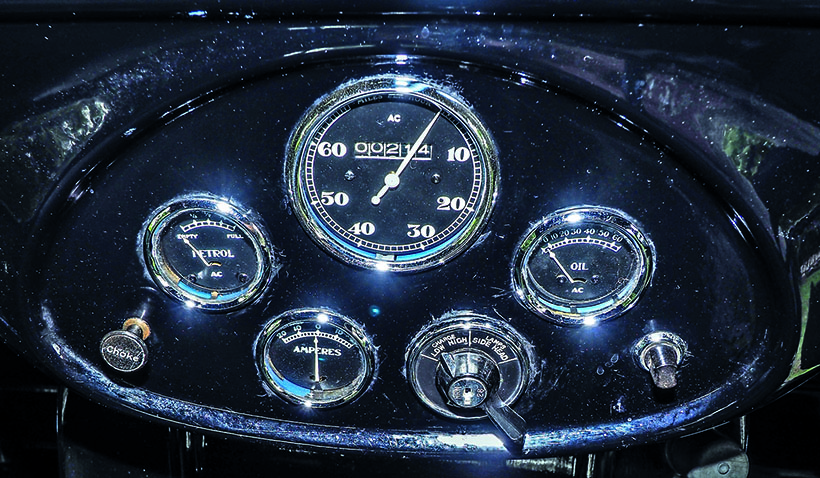

In terms of actual work needed, the cab was shot-blasted and required a fair amount of welding; the roof had become dented during the barn lay-up, which had allowed water to gather. Some work was also needed elsewhere; the doors needed some work, for example. As with the D Type, the welding and fabrication work on the WT was carried out, to an exceptionally high standard, by Roger Cartledge, an old friend. The cab interior was fully refurbished, the instruments all reconditioned and a new wiring loom was acquired and fitted.

The chassis was fully refurbished, and took a fair while to complete due to everything being seized solid. Just removing the shackle pins took around three weeks of dad holding a chisel and Garry hitting it with a hammer. Heat was also needed, of course, and perhaps unsurprisingly Garry did ‘catch dad a couple of times with the hammer.’ The springs themselves were refurbished and the kingpins renewed, along with most other wearing parts.

Body business

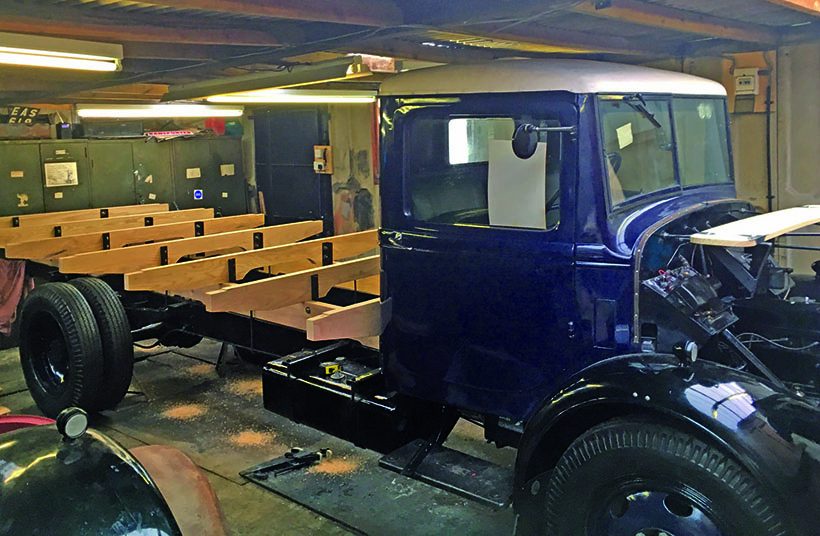

When it came to the body, a change from the lorry’s original specification was decided on – it came with the remains of a dropside body but, as a coal lorry, it would have been a flat, so as the aim was to recreate what would have arrived in 1938/9 had the war not intervened, what was left of the original body was dumped and a new replacement constructed. This was designed – and, for the most part, constructed by Alvar and Garry – though they had help with the runners and bearers, and Roger Cartledge handled the metalwork aspects.

As with the D Type, the WT was refinished using traditional coach-painting techniques, with Alvar doing most of the work and Garry the rest. Here, too, there was a slight ‘disagreement’ with the white roof being ‘the kind of thing they did then.’ Garry was not keen, though he now admits to having ‘come round’ to the idea. The signwriting was applied, again using traditional techniques by Andy Russell ‘a boat painter’ and, while the style is clearly in keeping with that on the D Type, it’s been cleverly and subtly back-dated to look more period on a pre-war lorry.

The project was finally finished in early 2019, with that year’s HCVS London to Brighton run its first trip out. Here, the pair were rewarded for their efforts with two prizes; a second in Class C (large vans and lorries built before 1940) and the Charles W Banfield challenge cup for the best restoration by a member of limited means. Now based with Garry on the edge of London, it’s also been to a few local events. As is usually the case with major restorations, a few niggles and teething difficulties have shown up, including a small amount of clutch vibration and a slight misfire under load. This is proving somewhat tricky to track down at present; so far, they’ve changed pretty-much every component in the ignition system and given the carburettor a thorough overhaul, all without success.

What’s my number?

One other, non-mechanical, issue also remains. Despite knowing so much of their lorry’s early history, there’s a lack of supporting paperwork; the original logbook is, it seems, long-gone, and all they have is some old tax discs that were left in the lorry when it was laid-up. Norfolk is also, unfortunately, one of the local authorities which followed DVLC’s misguided advice in the late 1970s to destroy old registration records following transfer to Swansea, and retain only a few pre-1920 records which were already of clear historic interest at the time.

The net result is that there’s currently insufficient evidence to persuade DVLA to reissue the original BAH 159 registration and, for now at least, the Bedford carries non-original mark KXS 417. They’ve certainly not given up on the battle to get back what clearly is the right mark as and when the rules change, or they come across any period paperwork which shows the BAH 159 registration and the WT’s chassis number and which will, therefore, be accepted under the current rules. Needless to say, any help that anyone can offer in this direction, would be very much appreciated.

for a money-saving subscription to Classic & Vintage Commercials magazine, simply click here