Brian Culpan reports on the sympathetic but thorough restoration of a 1947 Jowett Bradford van, and looks at the company that built it.

The Jowett factory was in Bradford, in the old West Riding of Yorkshire – Riding means a one-third. Yorkshire was a vast area so it was divided into smaller, more manageable areas called Ridings.

There was a north, west, and east but no south. The factory was just a few miles away from my childhood home. My father had a 1947 Jowett Bradford van for many years – so many, that as a young lad I helped him maintain and repair it and eventually became old enough to learn to drive on it! Consequently, Jowetts are at the top of my favourites list.

We visited the factory many times and I was promised a job there when I left my Technical Senior School – unfortunately it closed before I became 16! Later, at Bradford University my specialist tutor was a former Jowett engineer, he was a steady, meticulous, and methodical guy – reminiscent of Jowett's approach to engineering. I can still remember the long detailed discussions we had about independent front suspension and steering geometry; and how they both can fight for control of the front wheels.

Michael Kavanagh, a long-standing member of the Jowett Car Club, is a prolific collector and restorer of Jowett vehicles – particularly commercials. He is passionate about rescuing and reviving any Jowett vehicle. Often they have come to him in a dreadful state: only half there and that would be ‘far gone’. Fortunately, Michael has the skills, tools, and equipment to perform miracles. He had started a thriving motor repair business, Cavendish Garage in Keighley (now run by son Sean). This latest find is the type we all would love to discover (if only once in our lifetime).

Back in 1994, Michael heard rumours of a Jowett tucked away in a barn near the centre of Keighley. After making extensive enquiries over a considerable period of time; eventually, the barn was located and, its owner identified. Initially, he strongly denied there was a Jowett in the barn, but eventually admitted that there was; quickly adding that it wasn't for sale – as he was going to restore it.

Michael asked to see it, and after a bit of persuasion, walls of straw bales were removed to expose a very original Bradford van. It had been registered as FAK 246 with Bradford County Borough Council in December 1947. Its faded blue paintwork covered in surface rust but completely original, totally sound, and with only 26,319 miles ‘on the clock’. Just discernible, with patience, the livery reads: Rooks of 25 Church Street (known locally as Church Green) in Keighley, West Yorkshire, they sold hardware and earthenware (pots, pans cookware etc) – the first owners who used the van for local deliveries and collections from suppliers' warehouses.

In 1952, the engine developed a serious problem – frost damage. In post-war winters, many vehicles were taken off the road and put away, but if not, then precautions against the savage plummeting cold needed to be taken – or risk the consequences! My father used a very tiny paraffin lamp, its wick turned down to a minimum, placed under the sump; it was surprisingly effective – even outdoors. Alternatives were to place a large, thick army overcoat around the warm engine but remember to remove it before attempting any engine starting.

Another was to fully drain the cooling system – quite a chore as several draining points had to be opened in the case of a Jowett, each cylinder and the radiator and again essential that you don't forget to fill up next morning (so leave the radiator filler cap on the driver's seat). A plus for this technique was that warm water could be put in to ensure easy starting.

Early antifreeze solutions were very expensive, and since they are a very thin, searching, liquid that owners mistakenly thought caused leaks – it didn't but found any poor joints; they were not popular. In the case of this van, neglecting to take precautions led to serious frost damage after just two years and only 22,000 miles. Consequently, the owners ‘lost heart’, couldn't face the hassle of repairs. So, quickly sold locally to Wilfred Earnshaw, he did nothing but store the van in a dry barn. Fortunately, this storage was pretty well ‘dry’ the van had only slight surface rust – although this covered virtually every panel (during its decades of slumber).

Finally in 1994, he was persuaded to part with it, and it joined Michael's collection of Jowetts. Due to other projects, Michael did not start work on it but four years later sold it to his close friend Tony Palmer having been pestered by him to part with it for years. Unfortunately, Tony suddenly passed away four years later and his two sons took ownership. At the time, Michael tried to buy it back to no avail although he was promised first refusal if they ever decided to sell.

Eighteen years later, in January of last year, true to their word they offered it back – but not in exactly the same condition; the front wings, one rear wing, and bumper had been removed. Freezing had caused cracking in one cylinder and its head but both heads and cylinders had been removed and pistons dismantled! All explained as ‘first steps in the restoration process’. And, since the van had been stored in a cold, metal, shipping container; Michael feared for its condition. Surprisingly the bodywork, although covered in surface rust is sound.

Michael and Sean intend to quickly (months not years) fully restore the mechanical and electrical systems, fit a replacement fabric roof, and ensure that with new tyres, lights, and reflectors, it's road legal. The body and interior will be preserved in their present condition – what has become known as an ‘oily rag’ restoration.

On closer inspection, one cylinder was missing and the other (and its head) cracked, replacements were found from stock. The restored engine was back in by May 2020, and the grille and bonnet replaced. The two front wings were tatty and cracked in places, and so would require a lot of welding, so replacements were fitted (a broken rear stay was welded). The crumbling wood frame around one wheel arch required the skills of a bodybuilder; then the missing rear wing could be replaced.

The roof was now (mid-June) being re-covered in Oxfordshire, delayed by the virus outbreak. Hopefully when trade premises re-open, a new petrol tank will be fabricated locally. Frustratingly, a previous owner, in anticipation of a body-off restoration, had cut the wiring loom in several places. However, this was not needed as the chassis is in excellent condition – a new loom is on order.

The roof is a large a complex shape; slightly domed but with sharp corners – it's made up of multiple curved sections of differing radii. At that time no one in the car industry had the press power capacity to stamp out a full roof of this shape – even if taking several ‘strikes’ (strokes of the press) to attempt it. Simpler, large roof areas could be pressed but they were well rounded – egg-shaped like the Javelin saloon. The solution was to have about a 6in wide margin of metal around the edge with the large centre made up from soft waterproof fabric – this also prevented ‘drumming’ (a slow vibration of a large piece of thin sheetmetal). This margin provided a ring of steel to stiffen the flimsy body top, the chassis provided the same for the lower perimeter.

In true ‘Sod's Law’ tradition, the only serious rusting on this van has been a multitude of tiny pinpricks around the roof edges – the fabric had disintegrated long ago revealing these, but they are in the area essential for fixing to the frame! These edging pieces have complex shapes themselves; made up curves in two directions with tapering sections in the third. They could be hand-beaten in one piece, fabricated from several smaller pieces, or as in this case small enough to be pressed (and the tooling not too costly). Michael has opted for minimal repair to these to restore sound metal for fixing and limiting distortion by spot-welded new to old.

Original back lighting on the van was just a single D lamp with split lens to provide both a stop lamp and tail light (one piece red glass lens), a small clear side lens illuminated the numberplate). New regulations dictated that new vehicles from 1/1/54, and existing ones by 1/10/57, must have two rear lamps of equal power and appearance, and two reflectors of a certain minimum size were required Rear lights had to be within 24in of the body sides – two D lamps would just qualify.

Many simply added another D lamp at the other end of the numberplate leaving plenty of room for the reflectors on the small adjacent panels. However, the shop's owners added two Lucas angled plinth lamp units, intended to fit sloping rear wings of early post-war cars. The designer's intention was that their rear face would then be vertical. However, these had been screwed to the vertical back panels of the van, strangely angled at 45 degrees, and the van now had three rear lamps!

The small cab seats had been covered with hardwearing Rexine a forerunner of Vinyl (but only a driver's seat came as standard, another for the passenger cost a hefty £4 extra).

Following the Second World War, Jowett Cars, had detailed new designs; a futuristically styled saloon – the Javelin, and an equally exciting sportscar – the Jupiter but no money for development! It was decided to quickly update the old 8hp commercial range and get it into production rapidly to earn desperately needed funds. So, the Bradford was the result intended only as a stop-gap but became a best seller! Given a modified pre-war chassis and mechanicals but getting a new body designed by Briggs Motor Bodies and built at their Doncaster plant.

In a stroke of genius, the bodywork would be contracted out for two reasons, firstly the range was to be based on a commercial vehicle so styling wasn't that important, and Briggs would be free to design to suite their production facilities – which turned out extremely well. Jowetts themselves would modify the old 1930's chassis and enlarge the existing twin-cylinder engine.

To minimise costs and also weight (commercials were assessed for road tax on their unladen weight, cars on engine size) the ash framing was minimal, panels were of steel and aluminium, and fabric roof. Consequently, survivors usually have sagging, rotten bodywork – amazingly this van's is very sound, due to its short working life and careful storage. However, a small area of the timber frame has been replaced due to rot above one rear wheel arch, and two further rear pieces of the frame were replaced as a precaution. Over all, amazingly the body is exceptionally good. The tall body corner posts are steel pressings with flat body panels in aluminium.

The chassis construction is interestingly different. Rather than using a top hat profile, the same effect was created by placing one channel inside another some distance apart (both faced the same way, created a box section, and left an open face on the inside of the frame). These substantial fabrications were connected by four tubular cross members – bolted in position.

Vehicles of the time had just one wiper – the driver must be able to see but a passenger's view of the road – unimportant, and a passenger seat was not a standard fitting, so probably one would not be carried – so the thinking went. Also a single mirror was deemed to be sufficiently safe; cars had theirs mounted inside, commercials outside on the windscreen pillar. This one had been broken off – leaving just a short stem.

Over a working lifetime, Michael had acquired no less than 16 Jowetts, he eventually lost interest, sold most except a few (including the early, small, tiller steered car) but now is collecting again!

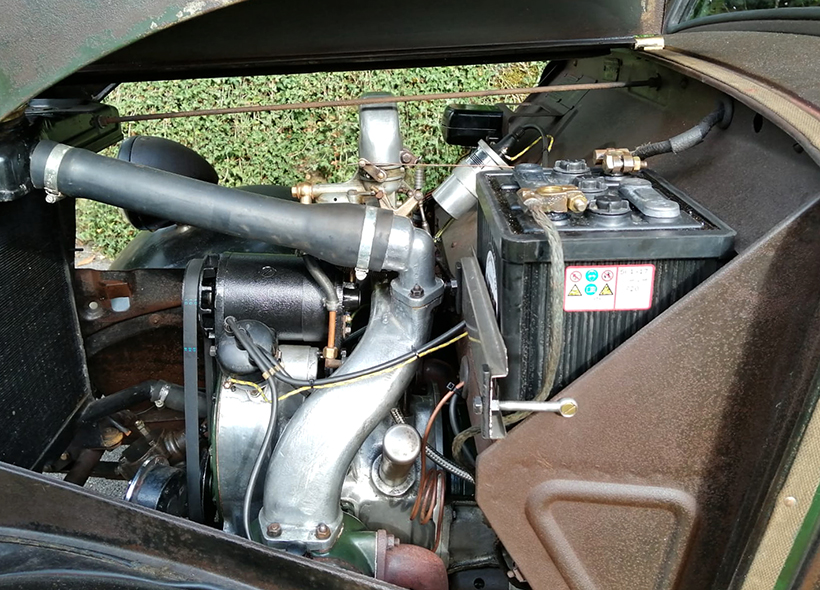

Lifting the piano-lid style bonnet sides, and looking at the engine I reckoned with a handful of spanners and a screwdriver, I could still take it apart. Despite all my father’s demonstrations of how easily the Bradford was to work (including some major strip-downs of engine and diff) I didn't pursue a career in the car repair trade but I have kept the old A/F spanners – just in case!

My thanks to Michael and Sean for spending time explaining the restoration work, and tsending photographs of the work. Also to Chris Spencer for additional photographs. And to Paul Beaumont of the Jowett Car Club for invaluable technical assistance.

Bradford models

This Bradford is a CB (C, Commercial, B, second series) replacing the almost identical earlier one in November 1947. The previous suspension, utilising half-elliptic leaf springs both front and rear, controlled by Girling Luvax hydraulic dampers, were all retained. The engine itself was the well-known two cylinder, horizontally opposed petrol unit with side-valves. Aluminium crankcase with cast iron cylinders and heads. It had been increased in size by enlarging the bores to 79.4mm, the stroke remained the same at 101.5mm, giving a new swept volume of 1005cc – the RAC rating, for taxation purposes, was still 8hp.

The engine only managed to develop 19bhp at 3,500 rev/min. but it was only lightly stressed and would go on forever – so it seemed. The horizontal layout partly disguised the fact that it had only the two cylinders by creating better balance. The engine and gearbox formed a unit, and was suspended at three points on rubber mountings.

The clutch bell housing and gearbox casing were cast in one-piece – a very advanced feature. Additionally, the top of the bell housing was left open to facilitate easy clutch adjustment. The camshaft was mounted above the crankshaft; this ensured that the tappets were easily accessible – on the topside of the crankcase. The tappets and valve springs were enclosed by a pair of removable covers. This fact allowed my father to change a broken valve spring on the forecourt of the York Jowett agent North Riding Motors; in just 30 minutes! Inlet valve stems were lubricated by a positive feed. A felt pad, held between inlet and exhaust stems, served to absorb excess oil from the inlet valve, and wipe some of it onto the exhaust valve stem. The only oil filter was a coarse gauze cover in the sump.

Several mechanical improvements had been made, they included: an external V-belt drive for the dynamo, which meant that the timing chain at the front of the crankcase, had to be adjusted by a jockey wheel sprocket – controlled by an external screw. The ignition coil was moved from the engine to the bulkhead. Provision was made for the fitting of a cooling fan, if required. The long induction pipe was shadowed by a water pipe – heated by the hot water on its way to the radiator. The Zenith downdraught carburettor was not normally fitted with an air cleaner on standard models, but one could be supplied as an extra.

The completed van will complement Michael's other Jowetts. Previous eye-catching commercial, concours, restorations have included a 1923 C cab long wheelbase van, a 1930 lorry, and a dilapidated 1950 Bradford van restored as a lorry – with authentic cab and loadbed. The 1923 ‘C’ cab van is the earliest known vehicle on the long wheelbase 7hp chassis found derelict in 1997 on a farm in Norfolk as a chassis.

Used as a shepherd's shelter with a tarpaulin canvas top added to offer protection from bad weather during the lambing season – pushed around on its wheel rims from field to field. The 1930 lorry was bought complete from a BBC producer but in desperate need of a complete overhaul mechanically; many new body panels and timber parts for the dropside loadbed were also needed.

The tatty 1950 Bradford van was first registered in the northern mill town of Halifax; thought to have started life with a market gardener. He must have been an important person – Alderman, Councillor, a prominent businessman, or had considerable influence to get such a distinctive number – the rest of us in Halifax just had to take the next number in the sequence! Michael was its third owner in 1989 and he restored it to magnificent condition. My very sincere thanks to Michael and Sean for their endless patience in answering all my questions and bringing the Bradford to a charming local location.

For a money-saving subscription to Heritage Commercials magazine, simply click HERE