Papworth Industries were one of Britain’s leading commercial vehicle bodybuilders, but with a unique benevolent aspect. Using photographs rescued from skips when the business closed, we begin a series telling the story of this unique business .

The story of Papworth Industries starts in 1916. Dr Pendrill Varrier-Jones, newly-appointed temporary county tuberculosis officer for Cambridgeshire, had the idea of a self-supporting ‘colony.’ Here TB sufferers could live under medical supervision. But they could also do paid work and support themselves without harming their condition. Initially based in Bourn, the colony was an immediate success. It won official backing, and in 1918 acquired Papworth Hall at Papworth Everard, five miles away.

Commercial Benevolence

Though employment terms and conditions were benevolent, the businesses were always 100% commercial. Papworth paid real-world wages, and sold its goods and services at market rates. Initially there was a carpentry and cabinet-making workshop, a boot-repair shop, a poultry farm, a fruit farm and a piggery. In 1919 it opened a print shop, bookbindery and trunk-making workshop The trunk-making business was established mainly thanks to the efforts of James Alexander Box. Box, saddler to the Royal Field Artillery, caught TB in 1918 and went to Papworth to recover. Using his skills and some family connections, Box was able to establish a leather goods making business.

The coachbuilding operation began officially in 1962, though vehicle bodies had been built from around 1947. That year Frank Jordan, head coachbuilder for the London GeneraL Omnibus Company before WW2, became head of carpentry at Papworth Industries. Through contacts, he secured orders to build 500 shooting brake bodies on the Austin 16 chassis. Later, 900 A70 Hampshire Countryman ‘woodies’ were built by Papworth Industries followed by more than 1500 A70 Hereford Countrymen. They also made some Bedford OB coach bodies as a sub-contractor to Duple, and in the 1950s were one of ten firms entrusted with building Green Goddess fire appliances.

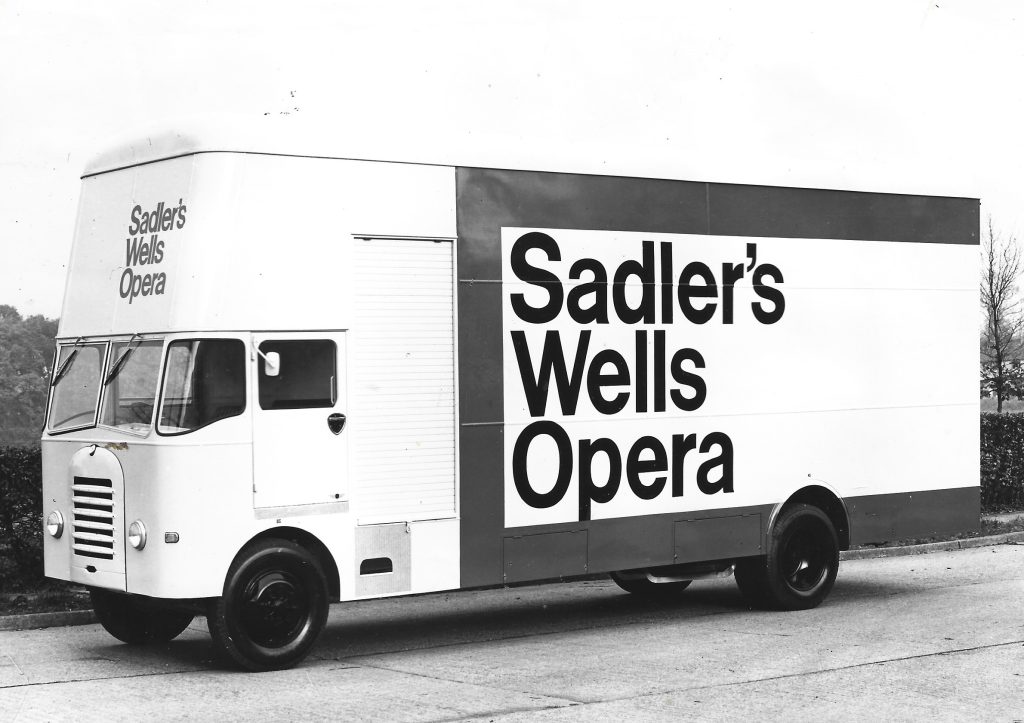

Other vehicles were made too. From 1962 the coachworks business became a separate entity, and an extremely busy one too. Most of the output was for state-controlled businesses; chiefly the GPO, MoD and British Road Services. However, Papworth Industries was not state-owned so it also supplied private sector businesses.

Papworth Industries coachbuilding operation continued into the late 1970s. As time went by the connection with Papworth hospital diminished somewhat. Additionally, with the virtual elimination of TB due to vaccination and changes in attitudes towards disabled people’s employment, the businesses all changed somewhat. Eventually they were all sold off into the private sector. The coachworks became ATT Papworth and by 2008 Papworth Specialist Vehicles, who went into liquidation in 2013. The premises are now used to manufacture safety and fuel delivery equipment.

Alan’s Memories

Alan Robinson joined Papworth in late 1961 as a 15-year-old apprentice. Due to the heavy nature of some of the work, the coachbuilding business employed a mix of disabled and able-bodied people. As wasn’t uncommon at the time, Alan’s father accompanied him to the interview. Then, when the letter arrived offering a position, it was addressed not to Alan, but his father. In fact Alan wasn’t mentioned by name; the letter referred to him simply as “the boy.”

Initially “the boy” spent four days a week on the shopfloor and one on day release at college in Cambridge. He didn’t much like the latter; it was, in his words, “like being back at school.” When he joined, all-steel and composite construction methods were coming in, but most of the bodywork being built was still wooden-framed. Papworth Industries were a ‘preferred suppliers’ list for state-run concerns. This meant they were generally made aware of prices offered by others and could match them. Many years later, Alan moved to local rival Marshalls for four years. When interviewed, he was told exactly what Marshalls thought of this arrangement.

Much of the throughput during Alan’s apprenticeship was Post Office vans and lorries. One consequence of the Beeching Cuts to the rail network was that much rural mail movement had to move from rail to road. Sometimes, if delivery of chassis was delayed, stocks of completed bodies would build up. He also remembers working on a batch of ‘Green Goddess’ fire appliances in 1962. Threse were abatch of 25, to the original 1950s design, for the Irish fire service.

High standards expected

Alan recalls that while Papworth standards were always extremely high, BRS specifications weren’t generally as high as organisations like the GPO and MoD. For example, BRS internal paintwork wasn’t generally so thick. They were also rather less fussy about material quality. For example while only ash or oak were good enough for the MoD and Post Office, BRS made extensive use of cheaper keruing. The Papworth complex included its own sawmill, and wood was delivered part-sawn or even as tree-trunks. Alan recalls that despite the keruing being delivered in very long lengths, he never saw a single knot. Apparently the trunks grow to up to 150ft high before branches start. There was, though, the odd lead bullet; keruing usually grows in places which weren’t exactly stable politically in the 1960s.

The GPO and MoD inspected every single vehicle before accepting it, and anything they weren’t happy with had to be put right. BRS, perhaps unsurprisingly, were happy to just come down every few months for a look around. These inspections were always thorough, but the inspectors “all had their particular obsessions” . For example, Len (nicknamed “Mr Austin Reed” on the shopfloor because he was always smartly dressed) hated seeing the slightest bit of swarf anywhere. He refused sign-off until it was removed. Another, named Harry, “talked a lot.” He also had a stock-answer when asked if there were any problems; “no, but you soon will have.” Quite what was meant by this Alan has never quite been able to fathom.

Very Fussy

The MoD inspector was particularly fussy. He would often run a finger along a row of round-head screws to ensure they were in straight and the same depth. He also once ‘snagged’ a run of paint from a spring hanger.

By contrast another inspector sometimes took Alan and some others to the pub at lunchtime. However he also generally asked if they could find him some spare wood or maybe a bit of wood-preservative for a DIY project at home…

Alan’s apprenticeship ended in 1966; apprentices received a pay-rise each year, and the final rise after five years took them to the usual skilled man rate. As time went on he rose through the ranks, first to Chargehand of a small group of skilled workers and then foreman. Among his duties was issuing staff with the parts they needed to do a particular jib, right down to the exact number of screws needed; the drawing office prepared lists of what was needed. He also had to know staff, and their individual strengths and weaknesses.

Changes

As he moved up in seniority, it was inevitable that Alan would have more day-to-day contact with management. At first, this was pleasant enough, as Papworth had a policy of promoting from within or, if someone had to be bought in, taking on only people with proven trade-specific experience. However as the 1980s moved on and the ATT era arrived, a new breed of manager started appearing; people with managerial qualifications but little or no trade experience.

Some of these didn’t last long. One such Alan recalls asking him why a particular person seemed to be taking longer than others doing similar tasks responded, on being told that the person concerned was slower for known health issues, responded “that is of no concern to me.” Another called in the foremen into a meeting and asked each in turn to explain their function. Alan replied “I make sure no-one runs out of bits.”

Eventually he tired of the politics and when applications were invited for voluntary redundancy, he applied and was accepted. He then spent four years working at Marshalls, but despite everything, still missed Papworth, and when the opportunity arose to return, he did so, and stayed until he retired in 2011.