Ed Burrows meets Alex Newcombe and his superbly-restored 1967 Leyland 680-engined Foden Blue Circle cement tanker.

Alex Newcombe loves power. His day job is working on 3,100hp Electro-Motive two-stroke V12 diesel-electric freight locomotives that run on the UK railway network. A chartered engineer with a degree in mechanical engineering and a master’s in railway systems engineering, since the age of 11 he's also been a heritage railways volunteer.

With his two best friends, he owns six 1950s/'60s-era 350hp English Electric-engined Class 08 diesel-electric shunters, a 1,000hp British Rail Class 20/English Electric Type 1 diesel-electric and a 1,750hp Class 37/English Electric Type 3.

With all that power to play with, you may well wonder why he’s restored a Foden 8L6/24 Blue Circle Cement tanker and a two-axle FG5/14 flatbed. Well, for one thing, you can’t take a rail loco home. Playing with trains at weekends meant less time with his family, whereas a truck can be worked on at home. And with trucks, the family can enjoy days out together at rallies and shows, which is where I got the tail end of the story that led to this article.

Chatting at last June’s Kelsall event with Malcom Sample, legendary conservator, restorer and fountain of knowledge about all things Foden, Mal answered my question about which he rated best in show among the assembled ranks of Elworth Works’ finest.

Would he choose the Shorrock family’s FG6/14, with four-door S20 cab? The epitome of concours condition, it featured in the August edition of Heritage Commercials. “It is faultless, absolutely magnificent,” Mal responded. “A professional, no-expense-spared restoration. It’s almost too good – probably better presented than any Foden that left the factory, unless it was a Commercial Motor Show exhibit.

“So – no. I’d award Alex Newcombe’s Blue Circle Cement tanker. All credit to him. He restored it himself, at home, parked on the driveway or at the side of the house, working in all weathers – and he finished it in only four years.”

Mal had been impressed by Alex’s first restoration, a 1959-registered S21 ‘Mickey-Mouse’ GRP cab 14-ton flatbed powered by an 85-/94hp five-cylinder Gardner LW. The two met when Alex was sourcing tyres. At the time, Mal was thinning-out his large collection of restored vehicles and saved-for-the-future projects. Most of the latter were languishing in an overgrown wood. Some had probably been saved and parked there when the trees were mere saplings.

Having been impressed by the quality and immaculate preparation of the 14-tonner – all the more because it was Alex’s first truck restoration and was accomplished in only a couple of years, Mal Sample decided he’d found a home for his S21 cabbed eight-wheeler.

Mal acquired it in 1989 from its second owner, a fairground operator. It was manufactured in 1968 and served with Blue Circle for about 10 years.

Alex Newcombe picks up the story: “Malcolm knew that what excites my interest are oddballs. By that I mean less-common specifications. The 14-tonner, for example, has a five-cylinder LW. So – a comparative rarity, rather than a specification of which any number have survived. The cab also has subtle moulding differences to later S21s, and it was factory-built with an interior in the style of an S20, not an S21.

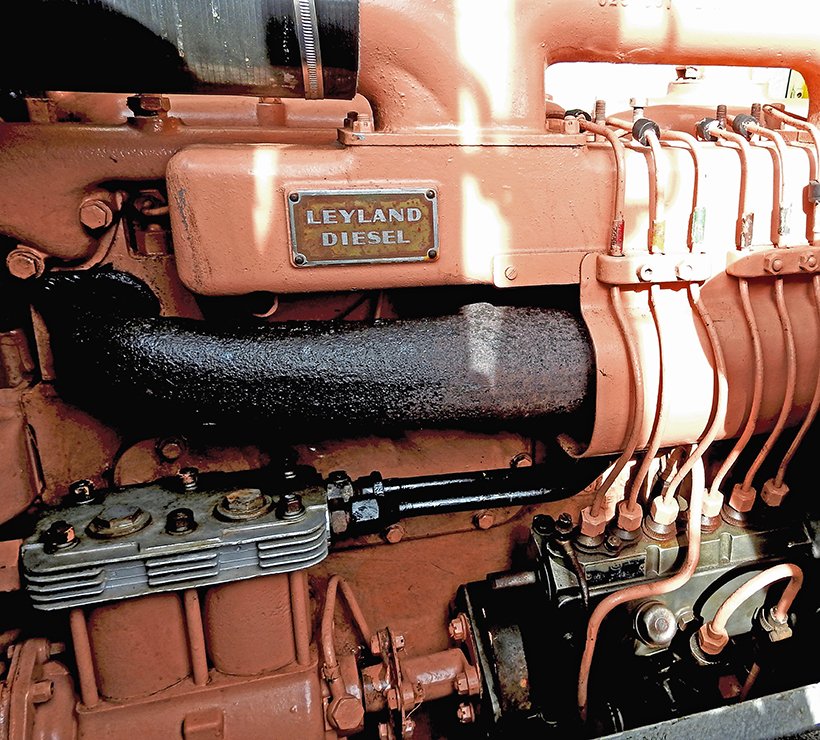

“The Blue Circle 8×4 has a 200hp naturally-aspirated Leyland 680 – again, not a common everyday spec. Mal knew that would appeal, and simply said: ‘I want you to have it. I know you will do a proper job, and you’ll finish restoring it in a few years, not decades.’

“Now ‘I want you to have it’ might sound like he wanted to give it to me but, of course, that wasn't the case. We made a mutually acceptable deal – and I knew Mal would help with advice should I need a bit of mentoring.

“It was recovered from Malcolm’s wood in 2018 and the restoration was completed last summer, in time for its Kelsall debut. The only part I hadn't finished was the tipping mechanism. The rams were in place, but the hydraulics weren't connected. It had taken four years and, in the middle of that, we had the disruption of the family moving house.”

Despite his career and hobby passion for diesel-electric railway locomotives, Alex Newcombe has always had an interest in trucks, influenced by having a grandfather who worked as a commercial vehicle maintenance technician.

When he first decided to take on truck restoration, he opted for the FG5/14 because, being a two-axle, he felt it would be an easier starting point for what he intended to become a hobby. He completed his degree-apprenticeship with British Rail Engineering and BR operated Fodens – hence the livery.

Alex rates Foden’s S21 cab as exceptionally attractive. He concedes that although 1633 RE has been restored as a flatbed, British Rail’s fleet never used S21 cabbed Fodens with this body type. In terms of authenticity, however, this is not too much of a stretch: BR operated 50-ton rated S21 cabbed Foden 4×2 ballast tractors.

Alex completed the two-year restoration project in good time for the 2019 wedding to his wife Louise and, for the drive to the reception, 1633 RE was the natural choice.

To put Foden’s initial glass-reinforced plastic cab design into context, five years before the S21’s introduction in 1958, Sandbach coachbuilder JH Jennings began production of the world’s the first GRP truck cab, ERF’s KV. In the same year, 1953, General Motors introduced the world’s first volume-produced GRP-bodied car, the Chevrolet Corvette. The KV was therefore at the leading edge of automotive innovation.

Considering GRP’s weight saving and superior insulation benefits – together with reduced manufacturing costs – it is pertinent to question why Foden was so off the pace.

The probable answer is that Foden’s product planning reflected the conservatism of its customer base, evidenced by the introduction only two years before the S21 of the S20, perhaps the UK industry’s ultimate aluminium-clad, timber-framed coachbuilt truck cab.

But traditional craftsmanship incurs a labour cost premium – and a new-build S21 weighted 168lb/76kg less than an S20. In sales, the balance gradually tipped in the GRP cab’s favour.

From 1962, Foden actually catalogued three cab options; the S20, S21 and the GRP/one-piece windscreen S24 – the UK’s first volume-produced tilt cab. Whereas Foden had been off the pace with the S21, with the S24 it gained the lead in cab design. When the coachbuilt S20 was de-listed in 1968, its sales were far behind the S21, which was withdrawn a year later. (The updated S34 version of the S24 and its subsequent evolutions continued until 1970.)

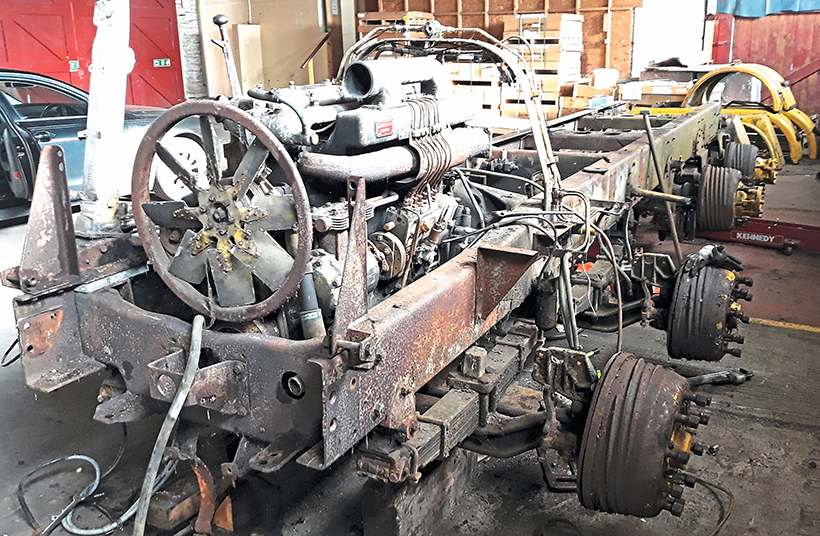

When Alex Newcombe went to recover ULU 809F from Malcolm Sample’s woodland hoard, there was a tree growing through the chassis. Cutting back the undergrowth revealed the chassis/cab in all its decrepit glory. Alex didn't underestimate what he was taking on.

The restoration straddled a house move. Alex did much of the work on the eight-wheeler on the driveway of the suburban house the family lived in at the time he acquired it. They subsequently moved to a detached cottage deep in the Cheshire countryside, where work was completed. Alex was fortunate in being able to complete some tasks – including the initial strip-down and, later, painting the tank – at premises in Stoke-on-Trent he had access to.

Discussing the condition of the chassis, Alex comments: “I dismantled it completely, right down to unbolting the cross members. Stripping down to bare metal revealed the chassis to be in very good condition, which is to be expected – after all it’s Foden steel. The only significant corrosion was where water had penetrated the ends of the cross members, at their junctions with the frame rails.

“Evidently to get a box-body to fit, the fairground people had lowered the mudguards of the rear bogie and the second steering axle to get them closer to the wheels. “They’d unbolted the mounting brackets and welded them in a lower position. I had cut them off, smoothed the welds and bolted them back in their original position.”

Alex really likes the engine. The naturally-aspirated, smooth-running, 11-litre, six-cylinder Leyland 680 delivers 200hp at 2,200rpm. “I took the engine and gearbox out and did a full strip-down overhaul. Apart from benefitting from new bearings, liners and piston rings, the engine was sound.

“The Foden 12-speed gearbox – a four-speed with an epicyclic splitter – was in remarkably good condition.”

As a professional engineer, Alex is perfectly qualified to pass judgement on engineering quality. He comments: “It is an honour to be the custodian of such a well designed and built vehicle. All credit to Foden – with one reservation. The let down was the cab. The GRP was mostly OK, but all the timber subframe was rotten due to moisture penetration.”

The S21 is an unusual combination of curvaceous tumblehome and flared surfaces, with the sides wider at the waist and tapered towards the roof. In consequence, the timber frame members aren't straight. Alex made templates in cardboard and planed them to shape. He explains: “As you would expect, the material I'm accustomed to working with is steel, not timber. I managed to obtain a template for the pillars of one of the doors, but not the opposite side. I made a template which, using a spot of engineering judgement, was right first time. In the interests of durability, I made the frame sections in sapele, and ensured they were properly sealed.

“The fibreglass cab front lower struts weren't reusable. This entailed making a mould and replicating.” Alex continues: “I obtained the pillar templates for one of the doors from John Sanderson – the go-to man for sourcing parts.

“Having set myself a target for completion – and some days being only able to give the project a brief hour or so of my time, there were various small items I decided it would take too long to restore, or fabricate replacements, or search for. Spending a fiver on a minor cab item such as a correct type of switch saved me massive amounts of time.

“Sourcing components and various items from John – including a fuel tank – proved an efficient and practical answer. Like Mal Sample, he is a mine of information and familiar with spec details for the most obscure bits and pieces. When the Foden works were being demolished, John Sanderson made umpteen trips to plunder and save archives – including engineering drawings – that otherwise would have probably gone to landfill.

“I cannot thank him enough, although for John, being a Foden fanatic, I guess his reward is seeing another Sandbach great restored and in sound working order.”

Asked about the braking, electrical and fuel systems and hydraulics, Alex responds: “Where d’you start? Not much was salvageable. All the rubber hoses were replaced, I rewired the electrics, fitted new brake cylinders and shoes, new copper pipe runs and learned my way round discovering – and analysing – what was wrong and fixing it as I went along. It’s a matter of attention to detail. Close examination, for example, revealed that two of the rear brake drums had been fitted on the wrong side.”

The big non-Foden bit is, of course, the aluminium bulk powder tank. As luck would have it, a friend of Alex spotted an ex-Blue Circle unit in Gravesend. It lacked pipework, had no end cap, and a new ladder and walkway would have to be fabricated. Inspection of the tank showed it to be fundamentally OK and with no major dents. A deal was concluded, and arrangements made for its delivery.

“The key parts that were missing were the tipping brackets and ram components,” Alex explains. “Fortunately, Malcolm Sample had a ram system. That left me with the job of making the tipping hinge brackets. Having amassed a vast amount of photographic reference material on Blue Circle bulk cement tankers, I was able to accurately replicate left- and right-side units.

“In terms of working it out as you go along, the two matching brackets were the most crucial items that had to be fabricated. I have to admit that, seeing them welded in place, I'm quite proud of them – you wouldn’t know they weren’t the original components.

“Again, the photographs I had accumulated provided the references I needed to accurately create the passenger-side access ladder and walkway plus its five supports, which are welded to the tank.

“The most time-consuming part of the entire project was sanding the tank back to bare aluminium. It took me two months. Don’t ask what it did to my fingers, but there was some compensation in that it revealed the position of the original signage.

“This equally applied to the cab. Carefully rubbing down the paintwork revealed the original fleet number and the signage on the cab front, doors and headboard.”

Discussing painting, Alex agrees it was a massive task. “After primer, I applied four coats of canary yellow. This presented a challenge I'd never expected; the colour attracted insects that got struck in the paint and drowned. That necessitated rubbing down when the paint was dry, then repainting in patches. The only way around the problem was to weigh-up the most favourable time to paint – taking into account factors like the air temperature, wind strength and direction as well as the amount of sunshine and cloud cover.”

I congratulate Alex on the paintwork and excellence of the overall turnout. He takes the complement modestly. “I don’t claim it’s perfect, but a professional paint job would have cost £10,000.”

Alex Newcombe readily concedes that spending most of his spare time working on the tanker wasn't easy on his wife, son and daughter, saying: “It wouldn't have been possible without Louise’s patience and support. During the course of the four years it took, there were times when the family thought the project would never end.”

The Newcombe family’s sacrifice equates to the price of the restoration. But what the world has gained is a genuine ex-Blue Circle powder tanker that’s as authentic as it could possibly be, and representative of a fleet that shifted up to 70% of Britain’s bulk cement.

The Leyland 680 sounds wonderful. The truck drives beautifully – though Alex accepts that the ride is bouncy, which could be cured by adding a modicum of ballast.

I point out to him that he’s younger than his S21s. We agree that’s unusual. People tend to like trucks they saw as kids, or their favourite drives during their career. The heritage community definitely needs more Alexes.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Heritage Commercials, and you can benefit from a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE